A podcast that explores Christianity and the political left provoked me to think again about Haiti this week. On March 9, I was interviewed about events in Haiti for The Magnificast, a podcast produced by my friends Dean Detloff in Toronto and Matt Bernico in St. Louis.

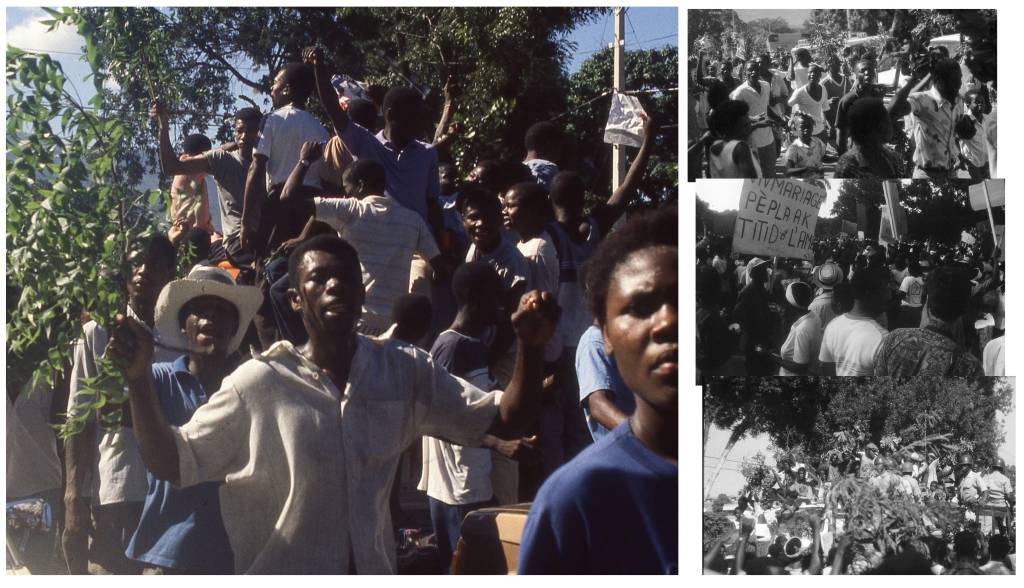

Right now, tens of thousands of people are marching in the streets of Port-au-Prince and other cities. They want to bring down the president, bring about a new interim government that would lead a process of constitutional reform, and organize new elections.

This time, however, they’re backed by a range of people and organizations that have not stood together since 1990 (Haiti’s first free election): churches, trade unions, community groups, students and teachers, the political left and centre.

The Magnificast has been a great space for me to think with others about complex events in Venezuela,Bolivia and now Haiti. The title is adapted from Mary’s song of praise, The Magnificat::

God has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;God has filled the hungry with good things,

Luke 1:52

and sent the rich away empty.

On March 8, a group of civil society organizations sent a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, calling for an end to Canada’s support for Haiti’s president, whose term of office has ended. Initiators of the letter were members of Concertation pour Haïti (CPH), a coalition of Quebec-based solidarity groups working in Haiti and individuals who support solidarity with Haiti. Members include The United Church of Canada (through its francophone ministries together with global partnership staff) and Development and Peace.

The letter calls on Canada, the United Nations and others to “consider transitional alternatives, without external interference, proposed by the various sectors of the opposition and civil society instead of blindly supporting the government of Jovenel Moïse.”

Over the past two years, Haitian organizations have proposed various ways forward. A transitional government should have taken office on Feb. 7, 2021, the date that the president’s term ended. The letter explains the next steps:

“A new government, accompanied by a transitional body, should hold office for at least two years. In addition, it would be established according to a specific institutional procedure, determined in a concerted manner within civil society and the opposition, which would ensure its limited term and its independence. The goal is to work toward the adoption of a new constitution in accordance with the wishes of the Haitian people, to prepare new elections, to adopt a plan to alleviate the population’s misery, to restore order in the public administration and to reinstate the judicial system.”

A day after the CPH letter, the Catholic religious communities that are part of the Haitian Religious Conference (CHR), used the occasion of the anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s visit to Haiti on March 9, 1983—three years before the end of the dictatorship of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier—to renew his call for change. “Il faut que quelque chose change ici,” the pope said, adding that impoverished people must recover hope. As he left, he encouraged unity: “Têt ansanm,” he said in Kreyol. All together.

“Thirty-eight long years after that visit by the pope,” states the CRH letter, “the seeds of death now seem to outgrow the seeds of life. The country is dying, insecurity is rampant, the poor cannot go on, the population is in a disarray that borders on despair, and the country is no longer ruled. We are both witnesses to and victims of too much crime, too much injustice, and too much inequality.”

So, what gives?

Some forces resist change. Haiti’s six richest families, together with a few thousand wealthy enablers, have shown through the past 40 years that they will resist any change whatsoever. And that class is well-connected to corporations and centres of power elsewhere. The United States, as elsewhere in Latin America, is arbiter of what can be done. It may have shifted from the Cold War-view that saw the Duvalier regime as a buttress against communism. The presidency of Bill Clinton in the 1990s imposed a developmentalist approach: Haiti would be a nation of cheap-labour assembly plants.

Since 2011, in the presidencies of Michel Martelly and Jovenel Moïse, the United States and the local elites have finally had the presidents they wanted: men close to the business sector and close ties in the United States.

But Haitians have other ideas. A few months after the 2010 earthquake, I was in Haiti with colleagues from The United Church of Canada. Among the people we met was Jesi Chancy-Manigat, a member of the coordinating committee of the National Feminist Platform. She was worried about the relief effort: “We are in danger of missing an opportunity.” It’s not enough, she added, just to consult with the president of Haiti. Civil society needed to be involved: citizens, organizations, women, workers, farmers, professionals.

Yes, the opportunity was missed, and Jesi, sadly, did not live long enough to attain the changes she wanted: she died from cancer in 2013 at the age of 57.

But she taught us a few things that those of us working for change now might keep in mind. First, listen to what Haitians say about themselves. Jesi introduced us to the work of the Kay Famn (House of Women) organization. In 2010, Kay Famn insisted that the country can be and must be rebuilt.

To rebuild the country is:

- To divorce ourselves from the practices of theft, corruption, dirty politics, and irresponsibility—where an executive or a Parliament can assume the right to ignore laws and rules.

- To have authentic dialogue with the people.

- To end the immense disorder that surrounds us: political disorder that prevents us from building a real democracy; electoral disorder that shackles the enjoyment of the rights of citizens; disorder in public administration, management of territory, justice, economy, education and health; disorder with respect to fundamental human rights, especially the rights to food, health care and housing.

- To re-deal the cards so that the state serves the common good, and so that people receive services and can produce and improve their well-being.

- To construct a system of social protection that permits action for the most vulnerable sectors: families headed by single women, those living with handicaps, those with low incomes, orphaned children, the elderly who have no resources.

- To commit ourselves to a path that moves us away from dependence on the exterior so that Haitians may take decisions according to national interest.

The demands today are not different from 38 years ago or 11 years ago. Yet, the people persist. And yes, we support their struggle.

More resources

An article in English by Marc-Arthur Fils-Aimé of the Karl Lévêque Cultural Institute (ICKL) and the Alternative Development Platform (PAPDA)

Position paper by the Jesuits of Haiti on the current crisis

“The Millionaires Of Haiti” Podcast