by Jim Hodgson

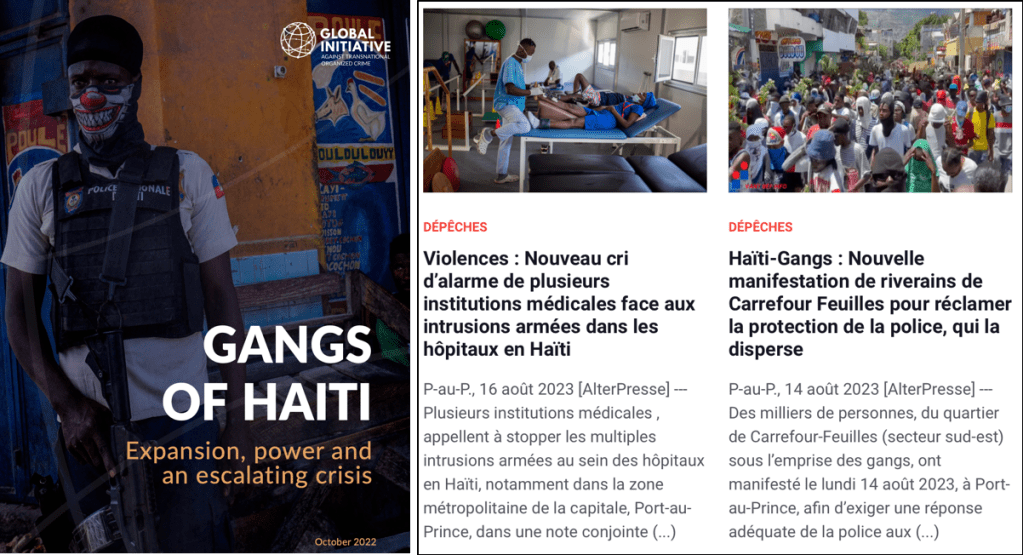

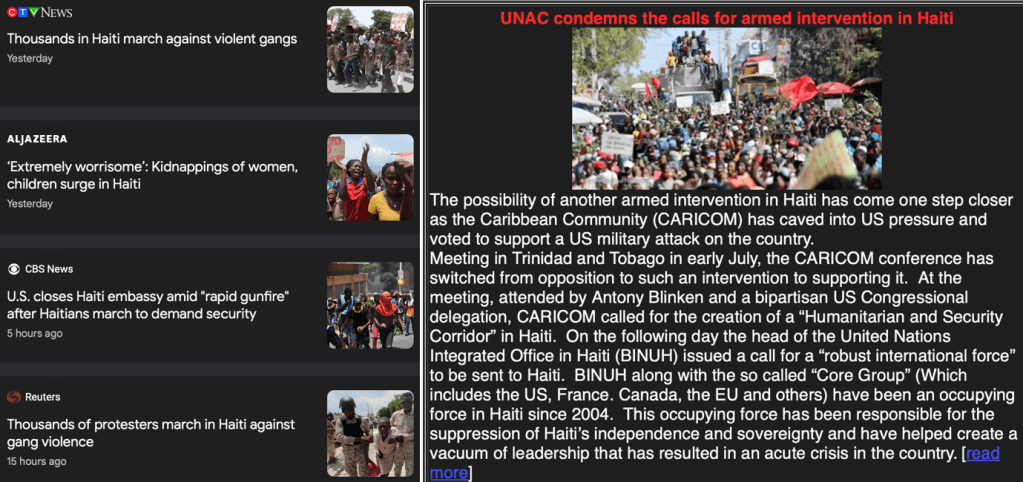

Over these past 40 years, I have understood that one of the hardest things for me to do is to talk about Haiti and the Dominican Republic in the same breath. Differences between these Caribbean neighbours are profound. I love them both and have developed strong friendships in both places. The relationship between the two countries is often made worse, both by xenophobic and racist politicians in the Dominican Republic, and the refusal of the international community and Haitian elites to allow an effective state to function in Haiti.

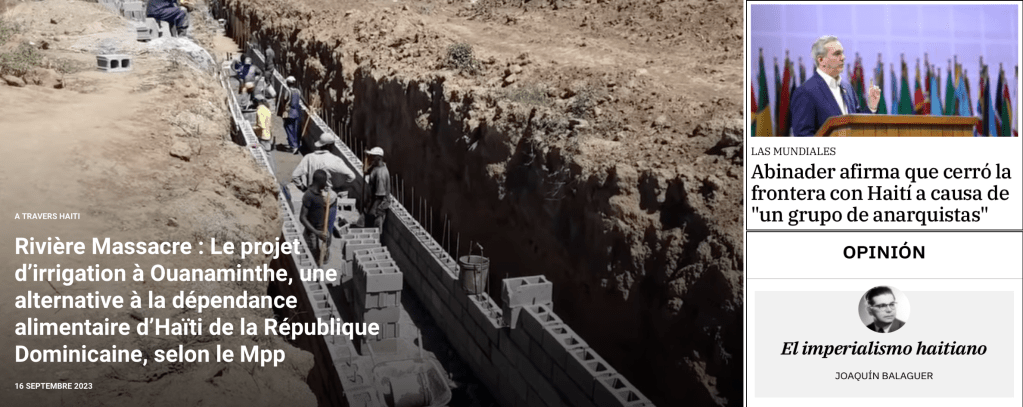

Dominican President Luis Abinader has now staked his re-election campaign on a quarrel with Haiti’s weak interim government over community efforts to build an irrigation canal from a river near the northern end of the two countries’ shared border.

Rio Dajabón (or Rivière Massacre in French) is only 55 km long. Its source is in the Central Cordillera of the Dominican Republic, but it has tributaries from the Haitian side as well. A series of treaties achieved between the two countries in the 1920s and 1930s are supposed to govern how waters are shared and disputes resolved, but the process is not being respected now.

When I first started visiting both countries back in the 1980s, most Haitians in the Dominican Republic were sugar cane-cutters brought over by a contract that saw the Dominican State Sugar Council (CEA) pay the Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier $2 million each year for the cane-cutters’ labour. This was, rightly, denounced as slavery. With the fall of Duvalier in 1986 and then the decline of the cane sugar industry (brought on by the United States’ preference for high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) produced from corn in its own factories), the practice ended. But Haitians still needed work, and Dominican industries (agriculture, construction and tourism) still need cheap labour.

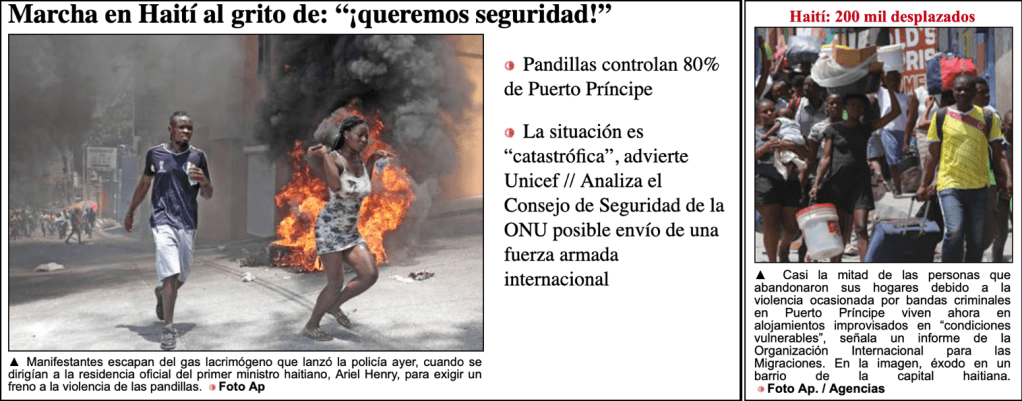

In fits and starts, successive Dominican governments have tried to force Haitians from the country, often with cruel, arbitrary measures. This past week, many Haitians rushed to get home before Abinader closed the border on Sept. 15.

“It’s really a very drastic measure that doesn’t make sense economically for either the Dominican Republic or Haiti,” Diego Da Rin of the International Crisis Group told Associated Press. “This will clearly have very bad consequences economically in the Dominican Republic, and it will very likely worsen the humanitarian situation mostly in the areas close to the border.”

Anti-Haitian campaigns in the Dominican Republic meet with some success because they echo traditional themes in Dominican history and culture. The problems which exist between the Haitian and Dominican peoples have roots in the colonial period. The colonial powers, Spain and France, divided the island between them in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick which was signed to resolve a European conflict.

A century later, a revolution by slaves in the French colony resulted in independence for Haiti in 1804. France fought a series of wars between 1795 and 1815 to recover what it had lost, and occasionally used the Spanish colony as a base for attacks on Haiti.

During the same period, Haiti invaded the Spanish colony several times. Some Dominican historians (including Joaquín Balaguer, a former president) say Haiti’s leaders in this period and later were imperialists who tried to win control of the entire island. Some more progressive Dominicans counter this position with the argument that invasions of the eastern part of the island were designed to prevent its use as a French base for attacks on Haiti.

Others say that Haiti’s new leaders proclaimed solidarity with their brothers and sisters who were still slaves in the Spanish colony. The invasions that took place between 1801 and 1856 came about because of a sense of solidarity based on shared class interests.

It is the 1822 intervention that has had lasting consequences. Haiti seized the Spanish colony, and freed the slaves. It launched a land reform program, redistributing lands held by the rich and by the church. Dominican historian María Elena Muñoz argued in a 1995 book that the people did not feel themselves to be Spanish and preferred to benefit from what the Haitians had accomplished in their revolution.

The occupation lasted until 1844, when the Dominican Republic won its independence in a rebellion against Haiti. While the rebellion’s leaders, particularly Juan Pablo Duarte, made clear that their movement was not aimed against Haitians because of their race or culture, his liberal views did not prevail in the new republic. Duarte was soon forced into exile, and the new Dominican leaders were more conservative and more fearful: they spent much of the next three or four decades trying to get their new country placed under a protectorate of some or other major power (especially Spain and France) for fear that the Haitians would come back.

It is in this period that anti-Haitian prejudice was born and talk of the “Haitian threat” began, because the interests of the elite classes were affected. But anti-Haitian prejudice based on the class interests of the wealthy could not catch on among the poorer classes, so it was disguised as racial prejudice. This had the effect that the elites wanted—division—and the anti-colonialist struggle was impeded.

The emergence of the Dominican state, brought about by the commercial class and perpetuated by other wealthy sectors, did much to damage the sense of identity which existed between oppressed people in the old Spanish colony and Haiti, a sense of identity which had been forged by the shared condition of slavery and the common enemy, European imperialism. Events of the past century—particularly the dictatorships of Rafael Trujillo (1930-61) and the Duvalier père et fils (1957-84)—have served to further isolate the two republics from one another, effectively creating two nations of people with differing views about each other and their places in the world.

You can look at that history and find triumph: the liberation of the slaves in 1804 and 1822, and the acts of solidarity and compassion that occurred after the January 2010 earthquake when the first assistance that arrived in Haiti was brought by Dominicans. But you also find tragedy, notably the 1937 massacre of at least 18,000 Haitians ordered by Trujillo.