In human rights work, one’s first duty is to those who are harmed. But once in a while, one of the murderers says something that seizes attention as it reveals again the full banality of evil.

This occurred during a hearing in Valledupar of Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (referred to in Spanish as JEP). It’s the transitional tribunal that was set up to prosecute the perpetrators of crimes committed during six decades of armed conflict between the FARC-EP guerrilla fighters and the Colombian state. This hearing focused on the falsos positivos, the false positives, that occurred just in the northern departments of Cesar and Guajira. In the country as a whole, Colombia’s armed forces kidnapped more than 6,000 young men, murdered them, dressed them as guerrillas, and then tried to pass them off “successes” in its war on “terrorism.”

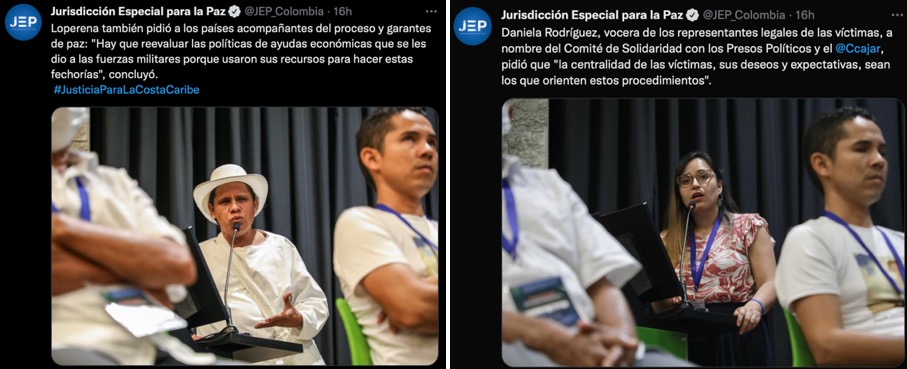

Others spoke for the victims:

When he spoke about aid to the Colombian military, Loperena was polite and understated the problem:

Over decades, the U.S. and Colombian governments have successively painted the war as: first, a war against communism; then, a war against drugs; and now, a war against terrorism. But the war in Colombia had its roots in the same struggle that has gone on in Latin America since the time of the European Conquest: the struggle by small farmers, Indigenous people and urban workers for land, social justice and basic human rights.

In the face of a peace process that has had limited support (and sometimes overt opposition) from the Colombian state, headed these past four years by Ivan Duque, that these tribunals continue to function is a triumph.

One of the hardest parts of achieving a peace agreement between the Colombian state and the FARC guerrillas was to find language about how to manage crimes committed by state and non-state actors during the conflict. The two sides began negotiating in Havana in November 2012. The agreement on transitional justice and reparations was achieved in 2015 and the full peace accord signed in December 2016. The former adversaries agreed to a form of transitional justice, creating special tribunals to judge crimes committed by both members of the FARC and by state agents.

It is not an amnesty, despite former president Álvaro Uribe’s characterization of the accord. In fact, that was what was avoided. Under international law that has come into force since the South African transition from apartheid to democracy in 1994, a full amnesty would not be legal.

Another triumph in recent weeks is the publication June 28 of the report of Colombia’s Truth Commission. Speaking July 14 to the United Nations Security Council, commission president Fr. Francisco de Roux said that Colombia has demonstrated that those wounded by war can come together to build peace, happiness and “produce a tomorrow where there is hope”. Over the last four years, the Commission has heard from more than 30,000 individuals and bodies and reviewed over 1,000 reports from victimized communities. He urged the international community to give Colombia “nothing for war.”

Top of the list of recent triumphs is, of course, is the election of a new president, Gustavo Petro, and vice-president, Francia Márquez. Like the truth commission, Petro has criticized the U.S.-led war on drugs. The truth commission has urged Petro to lead a global conversation on changing drug policies, with a focus on regulation over criminalization.

Petro and Márquez will take office on Aug. 7, and already there is talk of capital flight – in effect, a boycott of Colombia by rich investors, including Colombians who already have one foot in Miami. The road ahead – ending the alliances of military forces with paramilitary death squads and drug-traffickers, ending the practice of assassinating leaders of social movements (at least 145 in 2021), protecting rain forests and reducing the grotesque gaps between wealth and poverty – will be difficult as evidenced by this long (and nevertheless incomplete) list of U.S.-sponsored coups and invasions launched against left leaders in Latin America.