by Jim Hodgson

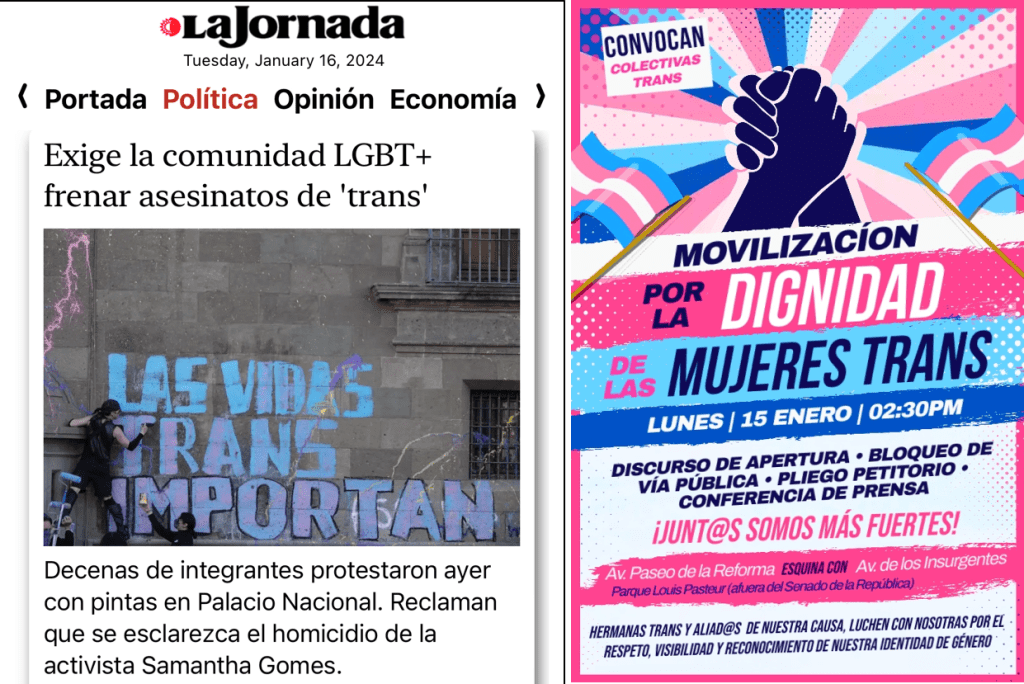

In Mexico, the new year began with a series of highly-publicized murders and beatings of Trans women. The violence, sadly, is not rare: Mexico follows only Brazil with the highest numbers of murders of LGBTQIA+ people each year. The fact that they’re being talked about at all is what’s unusual.

Two of the women who were killed were active in party politics. A woman beaten by her fiancé is a well-known social media “influencer,” Paola Suárez. The incidents are reminders of the breach between much-improved legal protection for LGBTQIA+ people in most of Latin America, and the harsh realities of day-to-day life where many men still hold to old ways. More on that below.

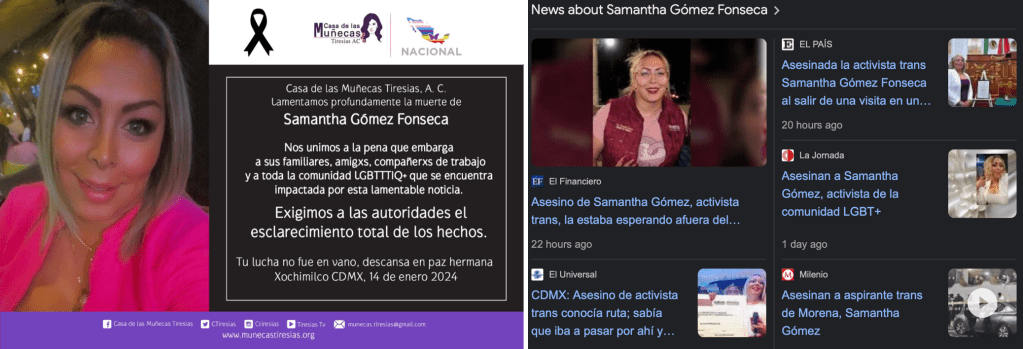

Samantha Gómez Fonseca, 37, had launched a campaign for a seat in the national Senate as a member of the ruling MORENA (Movement for National Regeneration) party. She was shot and killed on Jan. 14 in the street after a prison visit in the Xochimilco area in the south end of Mexico City.

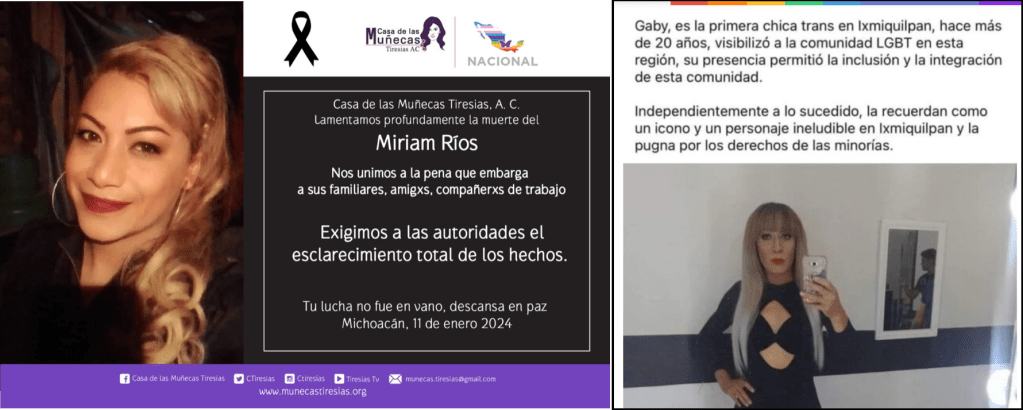

Miriam Noemí Ríos, part of the Citizens’ Movement party (MC) in Michoacan state, was shot and killed Jan. 11 in Zamora, Michoacan. She was a candidate for the municipal council in nearby Jacona.

“What is going on in Mexico?” demanded Salma Luévano Luna, a Trans woman who is a member of the national Chamber of Deputies for the MORENA.

“Why do we have four violent deaths of Trans women already this year? They’re killing us.

“This is what I am talking about when I say that hate speech is the entry point for hate crimes. For this, I demand justice for Samantha and all of my sisters. Enough. Not one more.”

Luévano had been in the news just days early after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador had referred to her as “a man in a dress.” He apologized a day later, and she accepted the apology, but the incident still rankles among Trans activists.

Others killed in the first two weeks of the year included Gaby Ortiz, whose body was found beside a rural highway near Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo. In Coatzalcoalcos, Veracruz, the bodies of Vanessa, a Trans woman and her partner (whose name is not given) were found in their home. The Arcoiris organization points to two more: a Trans woman whose name is not known found shot in the back and dead Jan. 13 in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, and a person identified as 35-year-old Fabián Kenneth Trejo, who died Jan. 14 in the Álvaro Obregón area of Mexico City.

“All of the victims, known and unknown, deserve justice,” said the Human Rights Commission of Mexico City in a statement Jan. 15. The commission called on authorities to investigate in ways that take seriously their gender identity and political activities “so that truth be known, leading to sanctions that are necessary for the transformation of the structural conditions that will allow LGBTTTIQA+ populations to live free from violence.”

From 2007 through 2022, a total of 590 Trans people were murdered in Mexico. That’s an average of 53 each year.

“To be Trans is to transgress the social order,” say the authors of fascinating essay, International Borders and Gender Borders, about the experiences of Central American Trans people among the migrants who are passing northward through Mexico. Trans people, they write, “challenge the heteronormativity of social and religious ways of thinking and being,” with all of their patriarchal norms and values. That system imposes a “binary, heteronormative” set of rules that try to restrict “each person within parameters that dictate gender roles, sexual orientation, and the spaces and tasks that are designated for each biological sex.”

That essay brought to mind two writers whose work is available in English. Neither is Trans, but both helped to shape my own thinking about gender, borders and identities.

When I was living in Cuernavaca in the late 1990s, friends recommended the work of the Chicana lesbian writer Gloria E. Anzaldúa (1942-2004), particularly Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987). Born in Texas, she lived her life across the U.S. southwest. Some of her gems, retrieved from the internet (as my copy of the book is in Canada and I am in Mexico):

“Culture is made by those in power- men. Males make the rules and laws; women transmit them.”

And:

“This land was Mexican once,

was Indian always,

and is.

And will be again.”

I would also suggest reading work by or about Marcella Althaus-Reid (1952-2009), who challenged the foundations of patriarchal Christian theology with her “indecent theology.” A hint: “All theology is sexual theology.” Here’s a good introduction from Kittredge Cherry.