Jim Hodgson

After being away for three years, I have returned to Guatemala to join a small Breaking the Silence team that will be looking into just one of a myriad of land conflicts that continue to afflict this country’s most impoverished people. I’ll write more about that in days and weeks ahead.

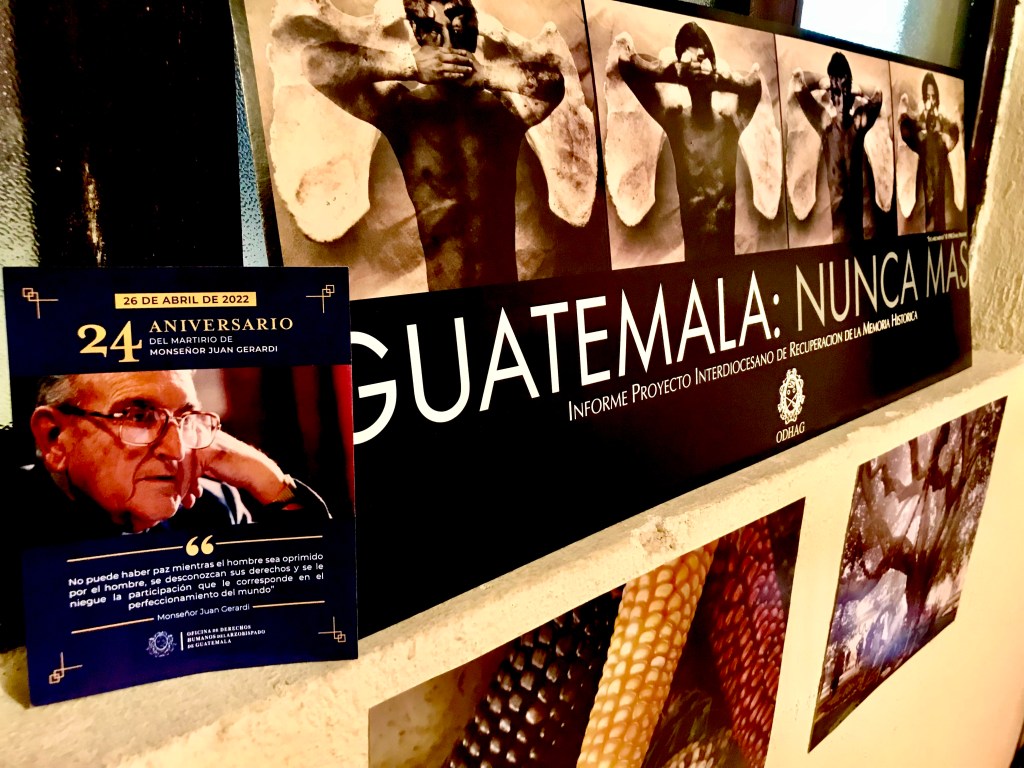

For now, I want to share some thoughts about the life and witness of Bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera(1922-1998), a man that I never met but whose friends have influenced me for decades.

From deep inside my venerable laptop, I found notes that I prepared on April 24, 2004, the sixth anniversary of his presentation of the report of the Catholic Church’s three-year Recuperation of the Historic Memory (REMHI) project entitled, Guatemala: Nunca Más (Guatemala: Never Again).

Gerardi was born in the Guatemalan capital in 1922. His biography says that at age 12, he “insisted firmly” that he wanted to enter seminary and to become a priest. His ordination came at age 24 in 1946. Over the next 20 years, he served as parish priest in several small communities and thus came to know the lives of Indigenous people and small farmers.

In 1967, he was named bishop of La Verapaz, a diocese that lacked economic resources but was rich in human resources. He worked with the Indigenous communities and organized courses for catechists, Indigenous pastoral accompaniment, and the movement of Delegates of the Word of God. Together, they organized liturgies in the Kekchi language.

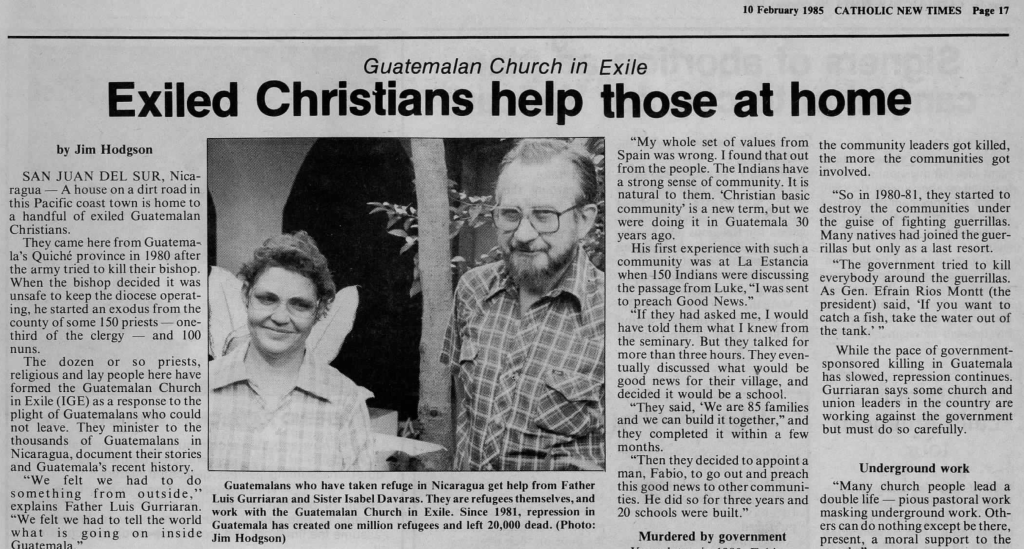

In 1974, he was named bishop of El Quiché, and that trajectory is better known. This was in the time that violence was increasing. In 1980, after the massacre of protesters in the Spanish embassy, military repression increased in all of Quiché. Violence against the priests and other pastoral agents of the diocese was so extreme that the decision was taken to close the work of the diocese. (See the image below of my 1985 article about the Guatemalan Church in Exile.)

Almost two decades later, he would present the REMHI report. After his own time in exile and return to Guatemala in 1982, he was named auxiliary bishop of the archdiocese of Guatemala in 1984, and that is where he worked to create the Office of Human Rights of the archdiocese (ODHAG), and where he began the work of REMHI.

Bishop Gerardi presented the report in the capital city’s Metropolitan Cathedral on April 24, 1998. This was 16 months after the peace accords had been signed, and in that context, the bishop said:

“Within the pastoral work of the Catholic Church, the REMHI project is a legitimate and painful denunciation that we must listen to with profound respect and a spirit of solidarity. But it is also an announcement. It is an alternative aimed at finding new ways for human beings to live with one another. When we began this project, we were interested in discovering the truth in order to share it. We were interested in reconstructing the history of pain and death, seeing the reasons for it, understanding the why and how. We wanted to show the human drama and to share with others the sorrow and the anguish of the thousands of dead, disappeared and tortured. We wanted to look at the roots of injustice and the absence of values….

“Years of terror and death have displaced and reduced the majority of Guatemala to fear and silence. Truth is the primary word, the serious and mature action that makes it possible for us to break this cycle of death and violence and to open ourselves to a future of hope and light for all…. Peace is possible – a peace that is born from the truth that comes from each one of us and from all of us. It is a painful truth, full of memories of the deep and bloody wounds of this country. It is a liberating and humanizing truth that makes it possible for all men and women to come to terms with themselves and their life stories. It is a truth that challenges each one of us to recognize our individual and collective responsibility and commit ourselves to action so that those abominable acts never happen again.”

While the report does not claim to include all the violations committed during Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, it documents 55,000 violations of human rights. A little over 48 hours after the presentation, Bishop Gerardi was killed. Perhaps more than any other event, this assassination highlighted the fragile state of human rights and the peace process in Guatemala.

One of those present in the Cathedral for the presentation was the Very Rev. Robert Smith, a former moderator of the United Church of Canada there on behalf of the Inter-Church Committee on Human Rights in Latin America. Bob wrote later about the great bells of the Metropolitan Cathedral ringing that day. He wrote that telling the truth about the genocide is essential to creating a new society: without this, “there can be no possibility of justice, healing or reconciliation.”

“Shockingly,” he added, “no more than five days later the great bells of the Metropolitan Cathedral were ringing again, this time as devastated Guatemalans followed the funeral casket…. Well, they can silence Bishop Juan Gerardi, beloved human rights defender and martyr. But they can’t un-ring the bells that barely a week ago celebrated the truth that some in the shadows of power do not want told. The sound of those bells – arrhythmic and at times discordant – is nonetheless the sound of un-utterable courage and unquenchable hope.”