Story and photos by Jim Hodgson

Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine is a massive failure of diplomacy and the oft-abused “rules-based international order.” Yes, President Vladimir Putin has done wrong. Sadly, most western countries failed to support recent diplomatic efforts by France and Germany or the earlier Minsk Accords.

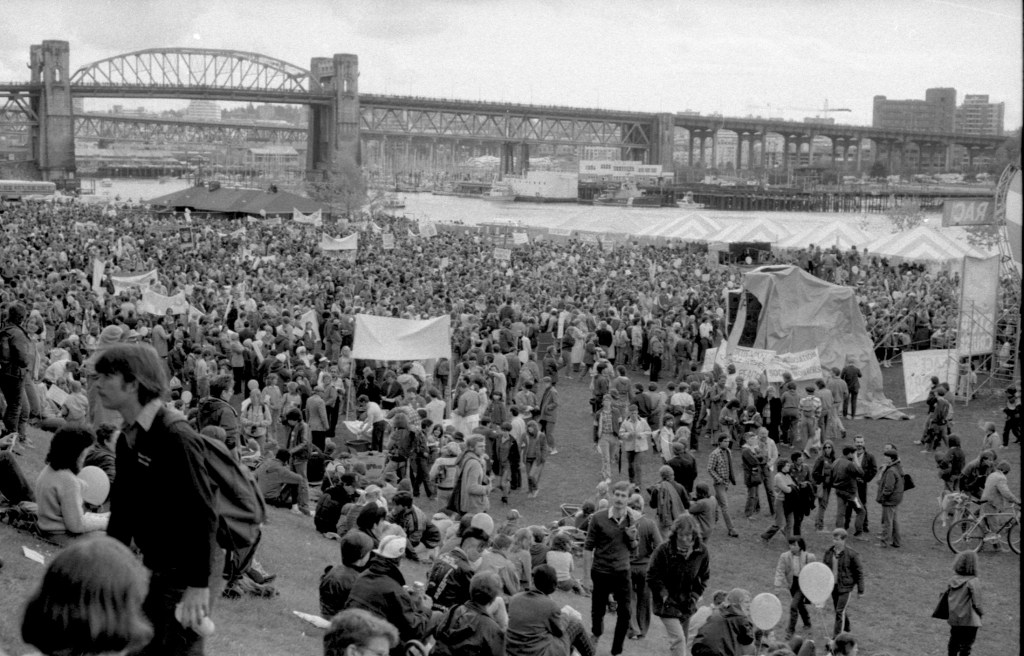

Decades earlier, we who were part of the massive peace movement of the 1980s failed to press hard enough for dissolution of NATO and for a fulsome welcome of Russia into the European Union and other multilateral spaces: Russia, in the eyes of the west, remained a foe, even after the end of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, we fell for the “end of history” nonsense promoted by the neo-liberal capitalists: it would be a unipolar world, with the United States defining how the rules would be applied.

That said, we just can’t have countries invading each other.

The UN Charter affirms self-determination in Chapter 1, Article 1 (2), and sovereignty in Chapter 1, Article 2 (1). Article 2(4) adds: “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State.” Those principles are at the heart of the rules-based international order.

Unfortunately, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council are pretty much immune from measures that could be applied to other states: they use their veto power to protect themselves or their client states in the wake of invasions and other interventions.

This time, in the case of Russia, the western powers are increasing levels of sanctions, with new announcements rolling out every day. The first round seemed weak, excluding such obvious measures as suspending Russia’s participation in the global SWIFT system for financial transfers or banning the purchase of Russian oil and gas. Five days later, some of those measures have been taken, together with suspending Russian access to airspace over many countries. The measures will bite. But whether their impact is greater on the rich and powerful or on ordinary people – or effectively aid Ukrainians in their struggle – remains to be seen.

I have done some work in recent years on negative humanitarian impacts of sanctions in so-called “less developed” countries (North Korea, Venezuela, Iran, Cuba, Zimbabwe, among others). I did not look carefully at sanctions applied among the United States, Russia and China against each other, or Canada’s sanctions against Russia and China (though I kept extensive notes). I have significant doubts about both the legality and effectiveness of most economic sanctions – “weaponized finance,” some have called them – whether applied by single states, groups of states, or the even UN Security Council.

The new sanctions against Russia represent a mix of what might be legal or not in public international law. Countries acting alone can restrict with whom they engage in trade and act to control their airspace. The UN General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council and various UN independent experts regularly denounce the illegality of “unilateral coercive measures” – sanctions – applied by one or more states against another outside the authority of the UN Security Council or other membership group like the African Union. General Assembly votes largely pit the United States, European Union, Canada, Japan and their allies against the majority world, the so-called developing nations. The December 2019 General Assembly vote on such measures was 135 in favour, 55 opposed, with no abstentions and three absent.

But, in this time of war, legal issues will only be dealt with later: for the moment, those with power make the rules. Where does that leave the rest of us?

At times like these, it’s useful to hear voices from outside the dominant North America/Western Europe political and media chatter.

Some people have correctly denounced the racism and hypocrisy reflected in much media coverage of present conflict. White Ukrainians are brave resisters, even shown on TV making Molotov cocktails, while any brown person doing that in southern Lebanon, Yemen, Gaza, Somalia or Afghanistan would be denounced as a terrorist or soon draw a drone attack.

One of the writers to whom I pay much attention is Raúl Zibechi, an Uruguayan writer on Latin America’s social movements – the Indigenous, peasant and urban movements that represent “los de abajo” – the under-classes, or those who are locked out of the formal economy and political power.

In an article published at the end of January, he cautioned such movements and their allies against choosing sides in “wars among the great powers.” Some people, he wrote, “think that it is better that the winners be those who oppose U.S. imperialism, which leads them to support Russia or China, or occasionally, Iran or any other nation that opposes the western powers.”

Social movements, he added, “should oppose war so as to deepen their own agendas” and “exercise autonomy and self-government, building other worlds that are new and different from the capitalist, patriarchal and colonial world.”

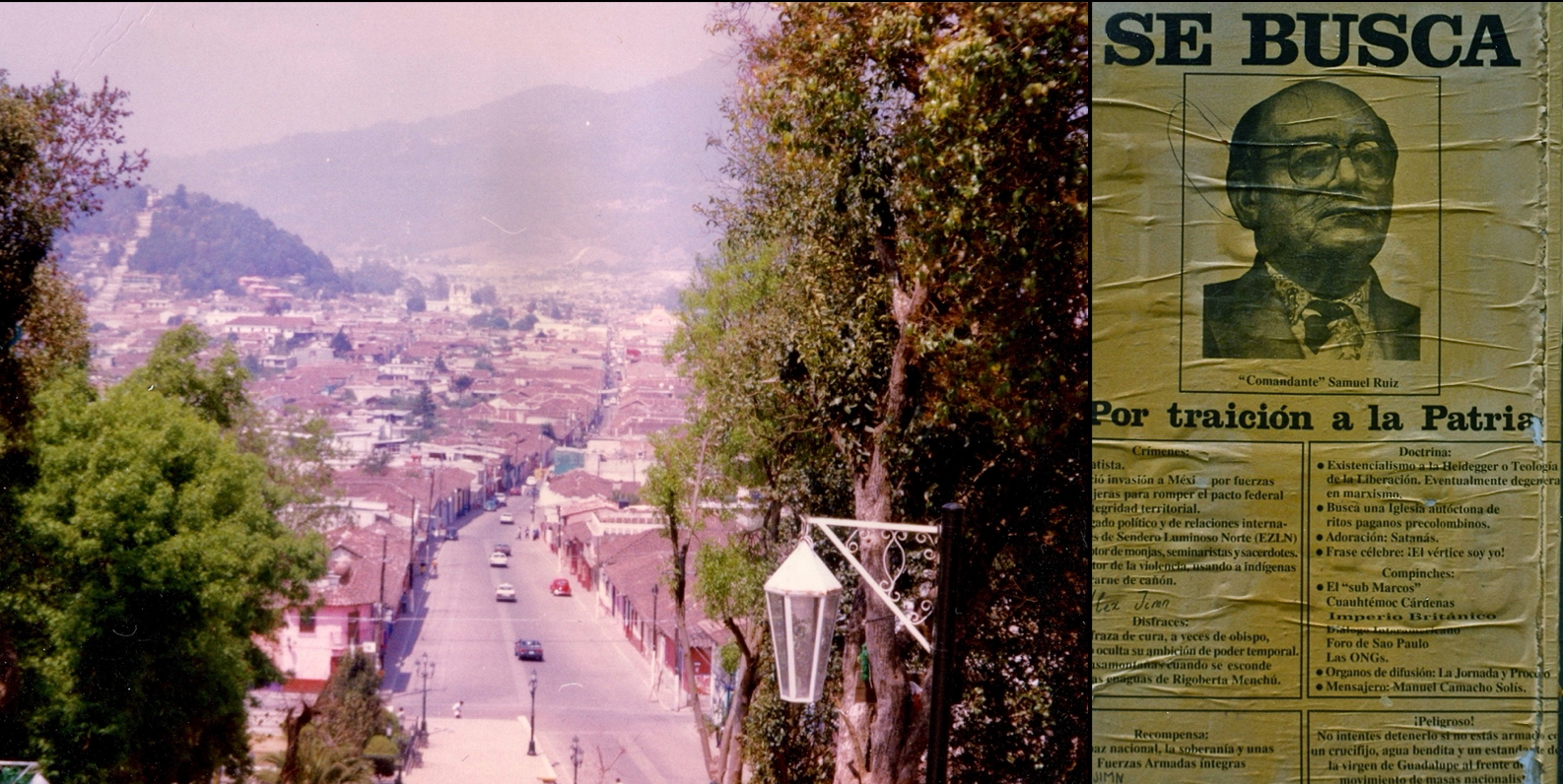

In several parts of Latin America, small farmers and Indigenous communities have had to learn to defend themselves against attacks from state authorities, drug-traffickers and large land-owners. Their self-defence, adds Zibechi, is not the same as “participating in a war that they did not choose.” Communities learn from the experiences of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, the Mapuche people in Chile, and the “ronderos campesinos” in Peru. “If we respond with violence (which ethically would be irreproachable), they [those with power] would take the initiative that they most want: the genocide of entire peoples, as has happened in the recent past.”

“The task of the peoples, in this time of wars among capital, is not to take power, but to preserve life and care for Mother Earth, elude genocides and not turn ourselves into the same as them, which would be another form of being defeated,” Zibechi concluded.