By Jim Hodgson

A modest step forward in the long struggle to end the failed U.S. embargo came this week when the United States removed Cuba from its short list of countries it alleges are “not cooperating fully” in its fight against terrorism. “This move… could well be a prelude to the State Department reviewing Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism,” William LeoGrande, a professor at Washington’s American University, told Reuters.

Until this week, the administration of President Joe Biden had made only minor reforms—easing some restrictions on travel and family remittances in May 2022—but had scarcely budged from the harsh measures taken by his predecessor, Donald Trump, much less attaining Barack Obama’s level of engagement.

It was just days just before the end of Trump’s administration in January 2021 that Cuba was added to the list of “state sponsors of terrorism” (SST)—because Cuba was hosting peace talks between the Colombian government and one of the guerrilla armies, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN). Despite occasional setbacks, the Colombian peace process moves forward slowly.

Biden’s new move comes after three years of non-stop advocacy by churches and other non-governmental organizations to end the embargo and to have Cuba removed from the SST list.

Efforts by churches, unions and other groups are driven by a sharp deterioration of the Cuban economy that is partly a consequence of the SST and other measures as banks and other corporations fear running afoul of the U.S. measures. The economic downturn is also related to reduced tourist visits to the country during the Covid pandemic and Cuba’s abandonment of its former two-currency system (one tied to the U.S. dollar, and the other that effectively subsidized local transactions).

In April 2023, an informal alliance of more than 20 Canadian churches, trade unions, development agencies and community solidarity groups wrote to Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly and to then-International Development Minister Harjit Sajjan to express alarm at the “deterioration of the Cuban economy and consequent impacts on the Cuban people.”

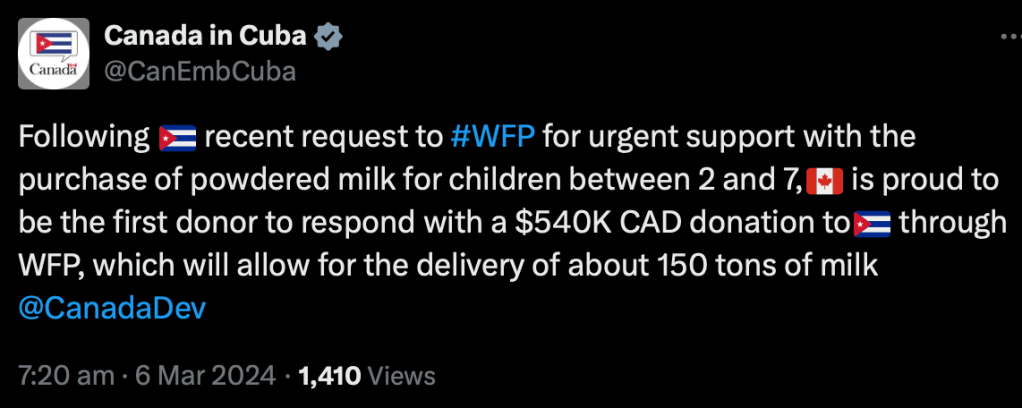

They called on the government to press the United States to ease sanctions and to remove Cuba from the SST list. They also asked that Canada “scale up its efforts to provide immediate food, medicines, and medical supplies to Cuba” (whether directly with the Cuban state or via NGOs and multilateral organizations).

The Canadian letter echoed earlier calls from Cuban and U.S. churches. In a joint letter sent Feb. 18, 2021, they asked Biden to to restore travel, remittances and trade with Cuba; to remove Cuba from the list of “state sponsors of terrorism;” to rescind Trump’s mandate to use extraterritorial provisions of the Helms-Burton law; and to rebuild U.S. diplomatic presence in Cuba. On March 13, 2023, more than 20 U.S. faith groups wrote to Biden to ask that Cuba be removed from the SST list.

The SST designation, along with Trump’s application of measures contained in the 1995 Helms-Burton Act, have extraterritorial impacts. Foreign-owned ships won’t dock in Cuba and foreign banks are reluctant to transfer funds for fear of running afoul of the U.S. laws. To understand better the impact of the SST in Cuba, please read a long report by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA).

The extraterritorial features of the Helms-Burton law provoked anger in Canada and Europe, but those features were effectively waived by Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama. In April 2019, Trump revived them. Canada repeated its objection, and reminded Canadians that amendments in 1996 to Canada’s Foreign Extraterritorial Measures Act (FEMA) stipulate that any judgment issued under Helms-Burton “shall neither be recognized nor enforceable in any manner in Canada.”

But Canada, to my knowledge, has yet to say anything publicly about the SST list.

Meanwhile, churches, NGOs and solidarity groups continue to provide aid to Cuba, including in response to damage caused by Hurricane Ian in western Cuba in 2022 and after the oil storage facility fire in Matanzas in 2022.

Vancouver-based CoDevelopment Canada is collecting material to send in a container to Cuban trade unions later this summer.