by Jim Hodgson

Beyond the constant babbling of That Man Next Door is a real plan for U.S. domination of the Americas.

The Trump administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy (NSS) says it will discourage Latin America and Caribbean nations from working with each other and with countries from outside the hemisphere. Overtly racist and nationalist, it also presses European countries to take “primary responsibility” for their own defence.

The document was released Thursday night (Dec. 4) and neatly summarized Friday night (Dec. 5) by U.S. historian Heather Cox Richardson:

In place of the post–World War II rules-based international order, the Trump administration’s NSS commits the U.S. to a world divided into spheres of interest by dominant countries. It calls for the U.S. to dominate the Western Hemisphere through what it calls “commercial diplomacy,” using “tariffs and reciprocal trade agreements as powerful tools” and discouraging Latin American nations from working with other nations.

“The United States must be preeminent in the Western Hemisphere as a condition of our security and prosperity,” it says, “a condition that allows us to assert ourselves confidently where and when we need to in the region.” …

It went on to make clear that this policy is a plan to help U.S. businesses take over Latin America and, perhaps, Canada. “The U.S. Government will identify strategic acquisition and investment opportunities for American companies in the region and present these opportunities for assessment by every U.S. Government financing program,” it said, “including but not limited to those within the Departments of State, War, and Energy; the Small Business Administration; the International Development Finance Corporation; the Export-Import Bank; and the Millennium Challenge Corporation.”

Should countries oppose such U.S. initiatives, it said, “[t]he United States must also resist and reverse measures such as targeted taxation, unfair regulation, and expropriation that disadvantage U.S. businesses.”

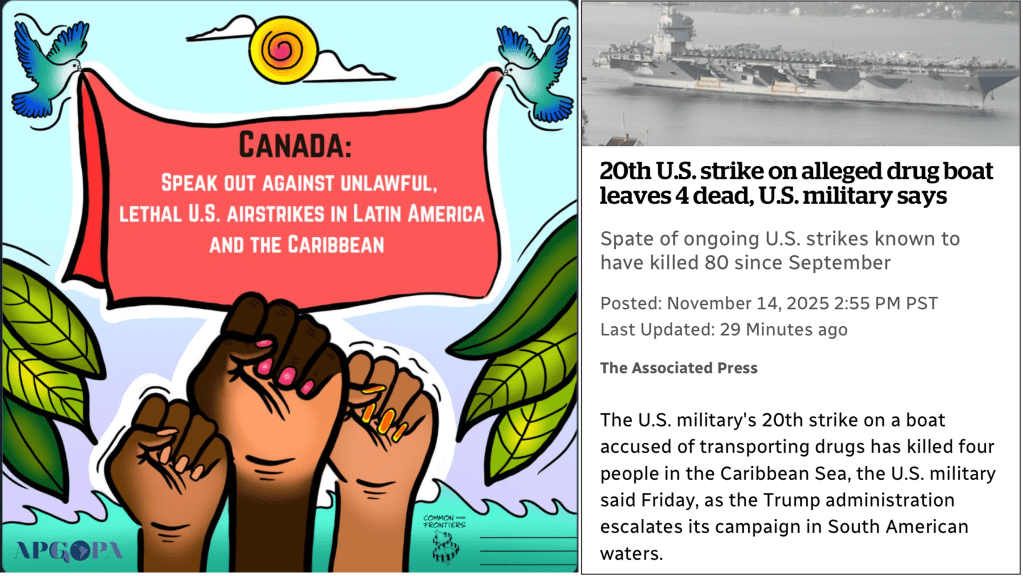

Think of it. The tariff fights with Canada, Mexico and Brazil. The stepped-up sanctions against Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. The mass murders of alleged “drug-traffickers” by exploding their boats in the open sea. Overt threats of “land strikes” in Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela. Trump’s interventions in national elections in Argentina and, most recently, Honduras. These are all part of the same strategy for renewed U.S. dominance.

I take my title today from the headline over La Jornada’s lead editorial Sunday, Dec. 7: Monroe nunca se fue. Trump’s policy (“Donroe”) rejects the polite notion of a “good neighbour policy” towards Latin America and the Caribbean promoted after 1933 by Franklin D. Roosevelt and others. But that approach was betrayed repeatedly by presidents from both parties who involved themselves in coups in Guatemala, Brazil, Chile, Honduras and elsewhere, along with invasions of the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Grenada and Panama – and the wars in Central America in the 1980s and U.S. support for paramilitary death squads in Colombia.

The people of Honduras went to the polls Sunday, Nov. 30. Before the vote, Trump did two things: he pardoned former President Juan Orlando Hernández, convicted last year in the United States for trafficking cocaine; and he endorsed the candidate of Hernández’s National Party, Nasry Asfura (known as “Tito” or “Papi”). A week after the vote, Asfura is in what election officials called a “technical tie” with a slightly more centrist candidate, Salvador Nasralla of the Liberal Party. Those two parties represent different factions of Honduran family oligarchs.

Whichever of them is ultimately declared the victor (a process that could take until Dec. 30), the ruling Libre party has been pushed aside. President Xiomara Castro had led the country for the past four years; her party’s candidate, Rixi Moncada, has only about 20 per cent of the official count – although many aspects of the election remain in dispute – including U.S. interference.

Key here is the coup On June 28, 2009, that ousted the elected government of Mel Zelaya, not quite a half-year into the administration of Barack Obama and his secretary of state Hillary Clinton. Their machinations brought about more than 12 years of rule that facilitated drug-traffickers, mining, corrupt land sales and human rights abuse – only partly subdued after the election of Castro four years ago.

“The abuse of force,” concludes La Jornada’s editorial, “is not, as [Trump] pretends, a sign of strength, but the recourse of one who cannot attract his neighbours with technological innovation, productive investment, exemplary institutions or a viable model of civilization.”