by Jim Hodgson

For the first time, Mexicans have chosen a woman to be their president. She is Claudia Sheinbaum, 61, a climate scientist who previously served as mayor of Mexico City.

That a woman is president is no minor detail. It was only in the middle of the last century that women in Mexico won the rights to vote and to run for public office. Even now, only 14 of 193 nations have women in power as presidents or prime ministers.

Sheinbaum can be expected to continue the generally progressive approaches taken by her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO). Her leading opponent was businesswoman and former senator Xóchitl Gálvez, candidate of a centre-right coalition.

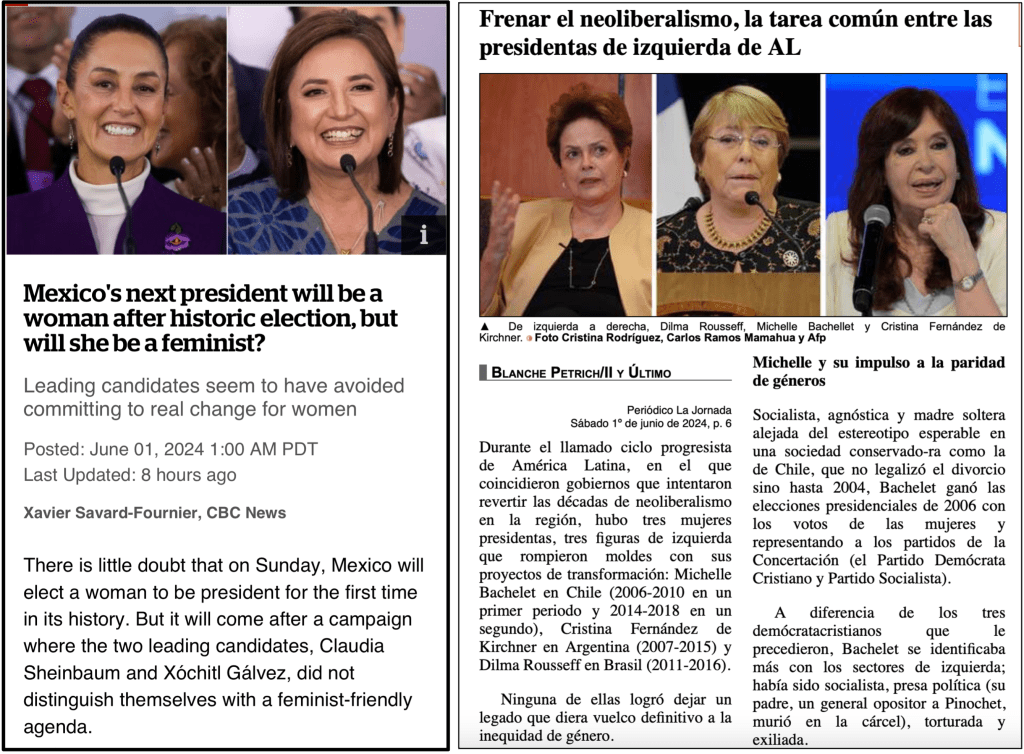

A CBC News report days earlier said that neither Sheinbaum nor Gálvez actually committed themselves to “real change for women” on issues such as pay equity, reproductive rights, or violence against women.

One of Mexico’s leading journalists, Blanche Petrich, wrote that three women (Michelle Bachelet in Chile, Cristina Fernández in Argentina, and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil) who were representative of the progressive “pink wave” governments in Latin America did not “leave a legacy that would definitively reverse gender inequality.”

Bachelet, notes Petrich, once said:

“What does it mean to be a woman in public office? Is it to be the same as a man, but with a skirt? No. When a woman arrives alone in politics, the woman changes. When many women arrive in politics, politics change. And clearly, one of the challenges and needs of our democracy is to improve the quality of politics.”

In the Mexican election, Sheinbaum and Gálvez tended to address issues of concern to women within a range of economic, social and criminal justice proposals. Framed this way, there were sharp differences between the two.

Sheinbaum will continue to give priority to social programs, pensions and scholarships that benefit the least advantaged, as well as concentrating on investment in infrastructure to support industries that create jobs. The approach by Gálvez was that of conservatives everywhere: keep taxes—and wages—low and let the market take care of the rest (though she did promise to maintain AMLO’s social programs).

At her victory celebration late Sunday night, Sheinbaum affirmed her movement’s commitment to democracy. “By conviction, we will never make an authoritarian or repressive government. We will also respect political, social, cultural and religious freedoms, and gender and sexual diversity.”

Regarding criminal justice issues (which media tend to subsume under the heading “security”), Mexico obviously has serious problems. At least 34 candidates were killed during the election period that included national as well as some state and municipal elections.

There are still about 30,000 homicides per year, though the government says the number has been dropping by about five per cent per year.

AMLO tried to turn back the violence unleashed by one of his predecessors. In 2006, then-President Felipe Calderón, with backing from the United States, launched a military-led offensive against the drug cartels to curb their violent turf wars. Instead, the violence became much worse.

AMLO promoted an approach he called “abrazos no balazos”–hugs not bullets. It meant addressing the social roots of violence by giving people the education and other resources they need to avoid being drawn into the drug-trafficking cartels and their systems of power. Over the long term, the approach should lead to reduced levels of violence.

But it has been controversial and is subject to manipulation, even in mainstream media like The New York Times, and has led to threats of military intervention from various U.S. politicians, including the presumptive Republican nominee, Donald Trump.

Even within the AMLO-Sheinbaum coalition, there is agitation. When Eduardo Ramírez–a former AMLO opponent who, like too many others, opportunistically shifted loyalties–celebrated his victory as governor of Chiapas Sunday night, he said: “There will be hugs, but no impunity.”