by Jim Hodgson

In a just world, news that Ecuador has banned its largest opposition party would be enough to scuttle Canada’s plans for a free trade agreement with the country – and even end U.S. military collaboration. But that is not the world we live in.

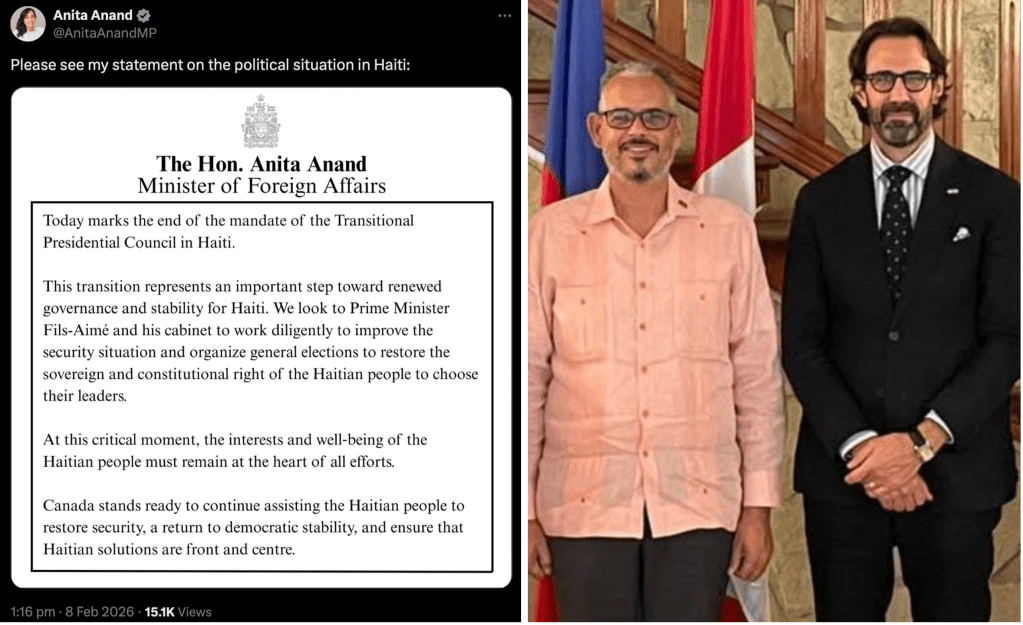

The news came as 77 organizations from Ecuador, Canada and around the world sent a letter to Canada’s ambassador in Ecuador urging the embassy to adopt Canada’s 2019 Voices at Risk: Canada’s Guidelines on Supporting Human Rights Defenders in response to the criminalization of Indigenous and environmental defenders. Among the signatories are MiningWatch Canada, Common Frontiers, and KAIROS Canada.

The letter to Ambassador Craig Kowalik was sent in response to the criminalization of Indigenous and environmental defenders from the Federation of Indigenous and Campesino Organizations of Azuay (FOA, Federación de Organizaciones lndigenas y Campesinas del Azuay).

FOA members are facing criminal proceedings for their environmental defense work to safeguard the Kimsakocha páramo from the Loma Larga gold mining project, owned by Canadian mining company DPM Metals Inc.

The letter to the embassy expresses concern over criminal charges initiated by DPM Metals against six FOA members — Lauro Sigcha, Lizardo Zhaqui, Marco Tapia, Ruth Pugo, Carmita Pérez, and Yaku Pérez — following a peaceful clean-up action to remove mining waste left by the company near the headwaters of the Irquis and Tarqui rivers in the Kimsakocha páramo. The Kimsakocha páramo is a fragile ecosystem that regulates the regional hydrological cycle and provides fresh water to tens of thousands of people. For more than 30 years, Indigenous and peasant communities have defended this ecosystem against large-scale mining projects.

Ecuador bans opposition party

Acting on the request of the government-aligned Prosecutor General, an electoral judge in Ecuador on Friday (March 6) ordered the nine-month suspension of the country’s largest opposition party, the Citizens’ Revolution (RC ).

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) denounced the ban as the latest escalation in a broader pattern of authoritarian regression, including lawfare against opponents, repeated states of emergency, and deepening military ties with the Trump administration.

“The government of President Daniel Noboa, who is strongly backed by President Trump, is trying to accelerate the destruction of what is left of democracy in Ecuador,” said CEPR Co-Director Mark Weisbrot. The move bars RC –led by former President Rafael Correa – from local elections to be held in 2027.

U.S.-Ecuador military strikes

On the same day as the ban on the RC party, the Ecuadorian and U.S. militaries conducted joint airstrikes near the Colombian border targeting a site allegedly tied to dissidents from the former FARC guerrillas from Colombia.

These “lethal kinetic operations,” as the U.S. military calls them, are another of Noboa’s efforts since his 2023 election to deepen ties with Washington — including a failed attempt to re-establish a U.S. military base in the country.

Days earlier, on Tuesday (March 3), the United States and Ecuador launched joint attacks against “designated terrorist organizations” – Trumpspeak for drug-traffickers.

Since September last year, the United States has attacked small boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, but these attacks in Ecuador are the first known land operations by U.S. forces against drug cartels. At least 150 people have been killed in 44 known strikes. The United States has never shown proof that any of the dead were in fact moving illegal drugs.

While neither government will say precisely where the attacks are happening, Noboa ordered curfews in four provinces west and southwest of Quito, extending to the city of Guayaquil and beyond. Noboa said his country was “entering a new phase in the internal war.”