by Jim Hodgson

If, as UN secretary general Antonio Guterres has said, the excessive debts of impoverished countries represent a “systemic failure,” then the solution would be reform of the system.

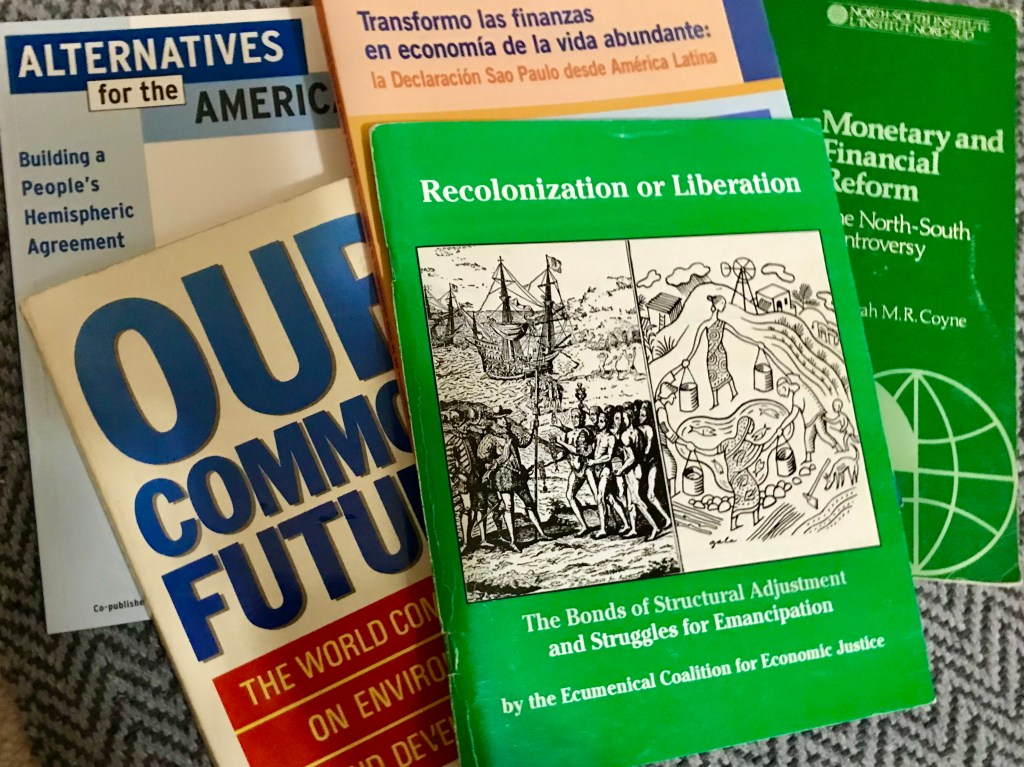

And so, for at least five decades, UN agencies, development NGOs and global justice activists like me have talked about a “New International Economic Order” (NIEO) or reform of the “international financial architecture.”

The latest tilt at the windmill of reform came in June from French President Emmanuel Macron working together with Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley. They invited world leaders to Paris June 22-23 to come up with a new “global pact” to fund the struggle to overcome poverty and human-caused climate change.

“What is required of us now is absolute transformation – and not reform – of our institutions,” said Mottley in her opening address. Mottley had earlier worked with other Global South nations to propose what is called the Bridgetown Initiative – a plan for changes to governance, policy and practice of North-controlled international financial institutions.

What followed, however, showed a “wide chasm” between what the Global South needs and what the Global North is willing to concede, said Iolanda Fresnillo, policy and advocacy manager for debt justice at Eurodad, an NGO focussing on debt and development.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio (Lula) da Silva, insisted that leaders address global inequality.

“It is not possible that, in a meeting between presidents of important countries, the word inequality does not appear: wage inequality, racial inequality, gender inequality, inequality in education, inequality in health. In other words, we are in an increasingly unequal world, and wealth is increasingly concentrated in the hands of fewer people, and poverty is increasingly concentrated in the hands of more people.”

With changes to taxation and provision of pensions, Brazil had lifted 36 million people out of poverty by 2010, he said. But after Jair Bolsonaro left office, 33 million were once again in poverty. Lula pledged to take steps again to improve the lot of the impoverished, to overcome deforestation in the Amazon and other forest regions of Brazil, and to collaborate with other governments for the sake of forests, climate and equity.

This August, Brazil will host a meeting of South American countries that share the Amazon basin. It’s a step toward 2025, when the Brazilian state of Pará will be the seat of that year’s climate negotiations, COP 30. Pará is where the Amazon River reaches the Atlantic Ocean.

But Lula also decried the ineffectiveness of global institutions that cannot enforce climate action and that represent the world as it existed in the late 1940s. “We cannot continue with institutions that work in the wrong way,” he said.

Western leaders “snub” Macron summit

Other than Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was the only G7 leader to attend. Canada was represented by then-International Development Minister Harjit Sajjan. (Sajjan was moved away from the development portfolio in the July 26 cabinet shuffle and replaced by Ahmed Hussen.)

But one searches in vain to find media commentary on Sajjan’s participation, and must turn instead to a government news release to find out what he said or did:

“While at the summit, Minister Sajjan participated in several high-level events, including an event on the key challenges, opportunities and tools required to achieve a new feminist financial architecture, as well as an event on increasing global investment in education to catalyze sustainable development. He also took part in a discussion on improving access to financing for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) through the Bridgetown Initiative and the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index. This discussion was particularly important to the Minister given his role of small states champion under the UN-Commonwealth Joint Advocacy Strategy for Small States. The Minister emphasized his commitment to amplifying the priorities of SIDS and helping to find solutions that work for them, particularly on climate vulnerabilities.”

Sajjan also announced that that Canada will invest $50 million in something called the BlueOrchard Latin America and the Caribbean Gender, Diversity, and Inclusion Fund “to increase access to financing for women, Indigenous peoples, Afro-Descendants and other underserved groups in Latin America and the Caribbean.”

BlueOrchard, the government news release explains, is “a member of the Schroders Group” and “a pioneer in the growing field of impact investing.” (Impact investing is defined elsewhere as an extension of socially responsible investing, and “goes a step further” by actively seeking investments that can create a significant impact.)

After a bit of digging, one learns that BlueOrchard Finance is a Swiss-based investment company that has been working in Latin America since 2007. It specializes in microfinance. “The strategy has financed 400,000 micro-entrepreneurs across 13 countries” in Latin America and the Caribbean. in 2019, BlueOrchard had about $3.5 billion in assets under management.

This is not the same as cooperatives, credit unions or even the microcredit “economy of solidarity”-style initiatives with which I have been involved in Haiti, Cuba, Guatemala and El Salvador. And it’s not about systemic change.

“Feminist financial architecture” and other good intentions aside, Canada and the other wealthy nations are part of a continuing failure to finance the fight against impoverishment and climate change.

A post-script. Global South leaders do not see issues in the same way that their Global North counterparts see them. In Brussels a few weeks after the Paris summit, European Union leaders held their first meeting with Latin American leaders in eight years. While the EU pressed for more support for Ukraine, Latin Americans led by Lula pressed for dialogue and questioned new European demands ahead of a potential new trade deal. In the end, the joint statement could only say that the ongoing war is causing immense human suffering and increasing the global economy’s real vulnerabilities.

2 thoughts on “Systemic failure of global finance demands system change”