by Jim Hodgson

A few nights ago, I watched the British actress Joanna Lumley in conversation with a group of homeless 14- and 15-year-old boys in Port-au-Prince. This was a scene in her 2019 documentary, “Hidden Caribbean,” about her travels in Cuba and Haiti.

I found myself thinking about similar conversations that I have had with teens in Mexico, Haiti, El Salvador and elsewhere: What about the gangs?

“They defend us,” said the teenage son of a woman I knew in La Estación, a neighbourhood where the train station used to be and near where I lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in the late ’90s.

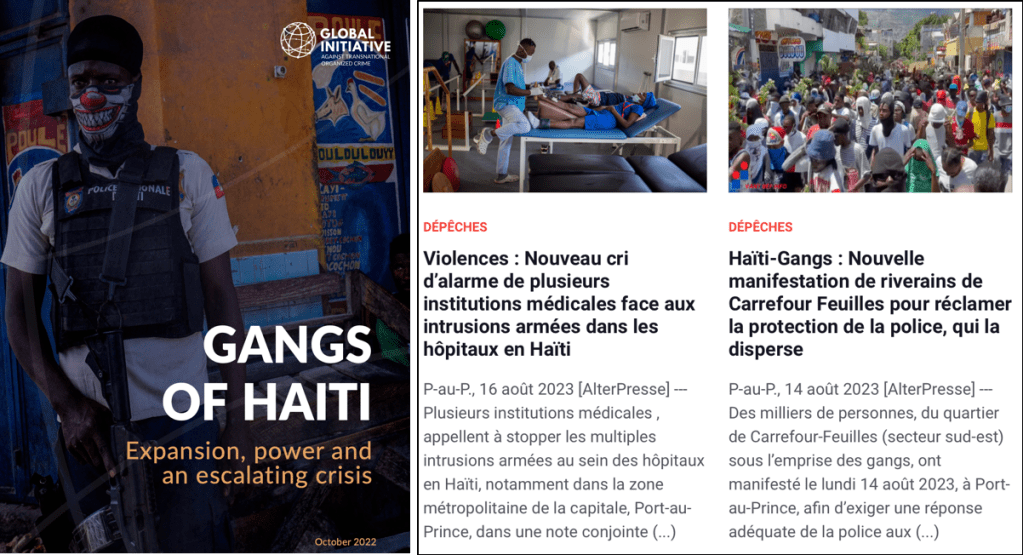

I’m not an expert on the sociology of gangs, but it seems to me that for unschooled, unemployed adolescent youth, they might provide a sense of team and friendship that in other places would be provided through schools, organized sports and other activities. And no doubt, there are people who manipulate younger people into activities to “defend” their barrio, and those then become fronts for extortion, drug-trafficking and kidnapping. (You can read more about the sociology of gangs of Haiti here and here.)

Criminal gangs are blamed for extreme levels of violence in and around Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital. Their actions become justification for calls from the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and others for an international intervention – this time with police forces.

A “robust use of force” by a multinational police deployment is required to restore order in Haiti and to disarm the gangs, UN secretary general Antonio Guterres said in a report to the Security Council Aug. 15. Such a force may be led by Kenya, and also involve police forces from several Caribbean nations.

“The longer that we wait and don’t have this response, we’re going to see more Haitians being killed, raped and kidnapped, and more people suffering without enough to eat,” said Ida Sawyer of Human Rights Watch a few days earlier.

By all accounts, the situation in Port-au-Prince is dire. On Aug. 17, Haitian aid groups backed by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) said they were temporarily shutting down operations, including some mobile health clinics, in the face of violence. Over the previous weekend, according to the UN, nearly 5,000 people fled their homes from areas around Carrefour Feuilles, Port-au-Prince. They are added to about 200,000 people displaced from their homes so far this year.

And more than 350 people are said to have been killed in lynchings by vigilantes since April.

You might think it’s progress that international actors are talking about police interventions rather than full-out military interventions after those have already failed in Haiti more than once. But decades of financial support and training of Haitian police (much of both coming from Canada) failed to overcome corruption and incompetence.

Much of this could have been avoided. Three years ago, a viable set of proposals emerged from a coalition of civil society groups – the Montana Accord, named for the hotel where their accord was signed. They offered a “passarelle” or series of steps for an interim government as a way to move to new elections. If the imperial powers – Canada, the US and France – had backed those proposals instead of Ariel Henry (the unelected “prime minister”) things might be different today.

Beyond the external powers, part of the problem is that the six richest families in Haiti don’t give a damn about the people or the violence, and prefer the current mess to a stronger and more effective state.

For now, the civil society groups continue to insist that theirs is the best way forward. There are various tables of negotiations to try to find a way forward. Some involve members of the Montana group and the acting prime minister.

I think too that, for the sake of peace, the gang leaders, who perceive themselves as defenders of their communities, may need to be reckoned with as political actors, not mere criminals. In July, Tom Hagan, a U.S. Catholic priest, said he had worked out an agreement with four gang leaders in the Cité Soleil neighbourhood. They committed themselves “before God” to “work to put an end to the violence and to bring peace to all peoples.” In the past, bishops have enabled similar agreements in El Salvador and in Guerrero state, Mexico.

I made my first visit to Haiti in 1984, when the dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier was still in power, and I’ve been back countless times since then. High points for me were in August 1987, when a massive popular movement seemed capable of wresting power from the military, and in December 1990 with the election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as president. What gives me hope is still the capacity of Haitian popular movements – workers, farmers, women, students – to organise and re-organise themselves for change, small and large.

What’s going on now in Haiti is a tragic mess that could have been prevented with some courage and imagination from the international community. In the first year or so after the 2010 earthquake, it seemed to me that the UN, foreign and Haitian NGOs, and the government of René Préval were working together toward a Haitian state that would be strong enough to deliver health, education, transportation, security, even land reform and other public services. But that was not the outcome sought by the United States and Haitian elites.

4 thoughts on “Cops, robbers and intervention talk in Haiti”