by Jim Hodgson

David, Kamill and I headed out by car last Monday for a quick visit to a small patch of territory northwest of our Okanagan home where a forest fire and an extreme flood wrought havoc just months apart in 2021.

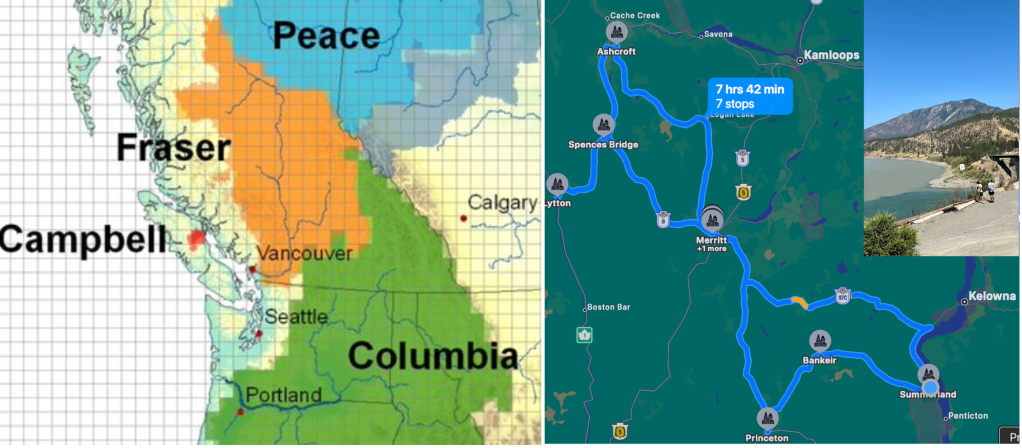

We drove west from Summerland on a beautiful mountain route that follows an ancient Indigenous trail—later part of the Kettle Valley Railroad and now a bike path—to just north of Princeton. Then we turned north to Merritt. From there, we followed the Nicola River northwest on Highway 8.

Centre: our route (the inset shows where the Thompson enters the Fraser at Lytton).

On Nov. 14 and 15, 2021, an atmospheric river brought an unprecedented amount of rain to southern British Columbia. All highways leading east from Vancouver and into the province’s Interior were blocked by floods or landslides. Princeton and Merritt were among many communities flooded.

The Nicola valley was particularly hard hit. It’s a narrow valley, and areas along both sides of the river were farmland. It’s home to the Nooaitch, Shackan and Cook’s Ferry First Nation communities and to their settler neighbours. The flood destroyed homes, farms, the old rail bed and parts of the highway. You can see the devastation of the Nicola valley in a Globe and Mail photo essay or in a B.C. highways department video. In November 2022 after a year of work, the highway re-opened with partial repairs.

As we drove towards Spences Bridge, we also passed through an area severely damaged in a forest fire some years ago. At the same time, we could see a new fire spreading on a mountainside ahead of us above the Thompson River—likely what came to be called the Shetland Creek fire.

We had lunch in a nice little restaurant called The Packing House in Spences Bridge—just next to the Baits Motel. We drove south on Highway 1 (the Trans-Canada) along the Thompson River to its confluence with the Fraser River.

And here we came to Lytton, the town of 3,000 people that was destroyed by a wildfire on June 30, 2021. Back in the late 90s, David and I began stopping here occasionally on trips to or from Vancouver. (We like to vary our routes.) It was a lovely town. It had a museum about the history of Chinese migration to the area—and its creator hopes to rebuild. Elsewhere in town, there is more construction: signs that the community will recover.

As we observed how the blue Thompson flows into the muddy Fraser, we could see a helicopter collecting water to drop on another fire burning in the mountains across the river.

We drove home via Ashcroft, whose residents are now on evacuation alert because of the Shetland Creek fire. After passing the massive tailings pond of the Highland Valley Copper Mine—a disaster of a different sort—we returned to Merritt and took the Okanagan connector highway to Peachland, and then turned south on Highway 97 back to Summerland. We drove about 600 km that day.

Of flood and fire

On Tuesday, Toronto had another “once-in-a-century” rainstorm after previous ones in 2005, 2013 and 2018. That day, we were back on Highway 97 as we drove Kamill to the airport in Kelowna for the trip home to Ottawa.

On Wednesday, a wildfire south of Peachland closed Highway 97 for most of the day. Traffic was later restricted to “single-lane alternating” (a phrase I am getting used to) and fully re-opened Friday afternoon.

As the week progressed (and U.S. climate-change deniers held their party’s convention in Milwaukee), I gathered some stories of effects of the climate catastrophe elsewhere in the world. (I did this in post back in January as well.)

Back in April, U.N. secretary general Antonio Guterres warned that “we cannot replace one dirty, exploitative, extractive industry with another” as we reshape how we power our societies and economies. Some developing countries have large reserves of “critical minerals” such as copper, lithium, nickel and cobalt. But they “cannot be shackled to the bottom of the clean energy value chain. The race to net zero cannot trample over the poor.”

In May, Raúl Zibechi, longtime observer of the role of social movements in processes of political change in Latin America, warned that the climate crisis cannot be stopped. Politicians won’t act for profound change; those who prefer wars over struggles for peace won’t change. His suggestion is that impoverished or otherwise marginalized peoples (“los de abajo”) build collective “arks.” The rich and powerful (“los de arriba”) already have theirs. The example he points toward is that of the Zapatista movement in Mexico’s southern Chiapas state, where for 30 years Indigenous communities have been living in a mostly self-sufficient and self-governing way.

Summers were always hot in the Fraser Canyon and up along the Thompson River towards Kamloops, just as they are where I live in the Okanagan valley. But it feels different now. There were always forest fires, but I don’t remember living in dread of them or having to put up with the long smoky days we have now. In the winter, there were cold spells, but I don’t remember the peach and grape crops being wiped out as has happened this year.

We are putting our emergency kit together (as we did last year) and placing all the important documents in one metal box. North American-style, I suppose: it’s an individualist sort of “ark.” We’re okay with having to take these steps. But we’re also talking about the election in B.C. later this year and a likely national one next year. How do we recover momentum for the dramatic changes necessary to carve a new way forward?

Thanks Jim for an excellent summary of the way things truly are here in what I now call “the province of fires and floods.” Also appreciate the detailed local accounting, including Lytton; also the comparison with the business-as-usual practice of the GOP and Trump, and to a significant extent democrats in the US. I join you with serious skepticism about how Canadian politicians and parties will advocate for real change in our own political, business, social, and environmental practices. Sure, we can all keep making money, and lots of it, through fossil fuel extraction, transmission, and combustion. Your concluding question is very much to the point, though I am not sure we are “recovering momentum” of a restorative process many have not yet themselves commenced.

LikeLike