by Jim Hodgson

In April 2024, I welcomed the formation of Haiti’s transitional council (known as the CPT). It was the product of negotiations among a broad spectrum of Haitian political parties and civil society organizations, including the business sector.

Within a month, fractures that would block steps toward a new election became apparent. And efforts to create conditions for an election were undermined by a rapid and ongoing increase in neighbourhood-based gang violence – despite the presence of UN-backed soldiers and police.

The mandate of the CPT expired on Saturday, Feb. 7, which also happened to be the 40th anniversary of the fall of the Duvalier family dictatorship.

A U.S. warship and two Coast Guard ships sit in the Port-au-Prince harbour and a military plane was on the ground at the international airport. As many as 1.4 million people are displaced by gang violence. The political in-fighting rages.

In moments like this, I try to look at a variety of media sources to understand what is going on. The one I trust most is AlterPresse, a civil society initiative that emerges from among the groups that have worked for decades for a better future for people afflicted by poverty and violence. Haitian elites and their neoliberal allies abroad, meanwhile, seem determined again to impose a new totalitarian state, which is a predator state (like that of Duvalier) safe only for the rich and their cronies.

In the absence of any elections, Prime Minister Alix Didier Fils-Aimé (a businessman named to the post by the CPT in November 2024) will hold on to power beyond the CPT’s expiry. He will rule like former de facto Prime Minister Ariel Henry did from July 2021 through February 2024: a head-of-government without a head-of-state or Parliament.

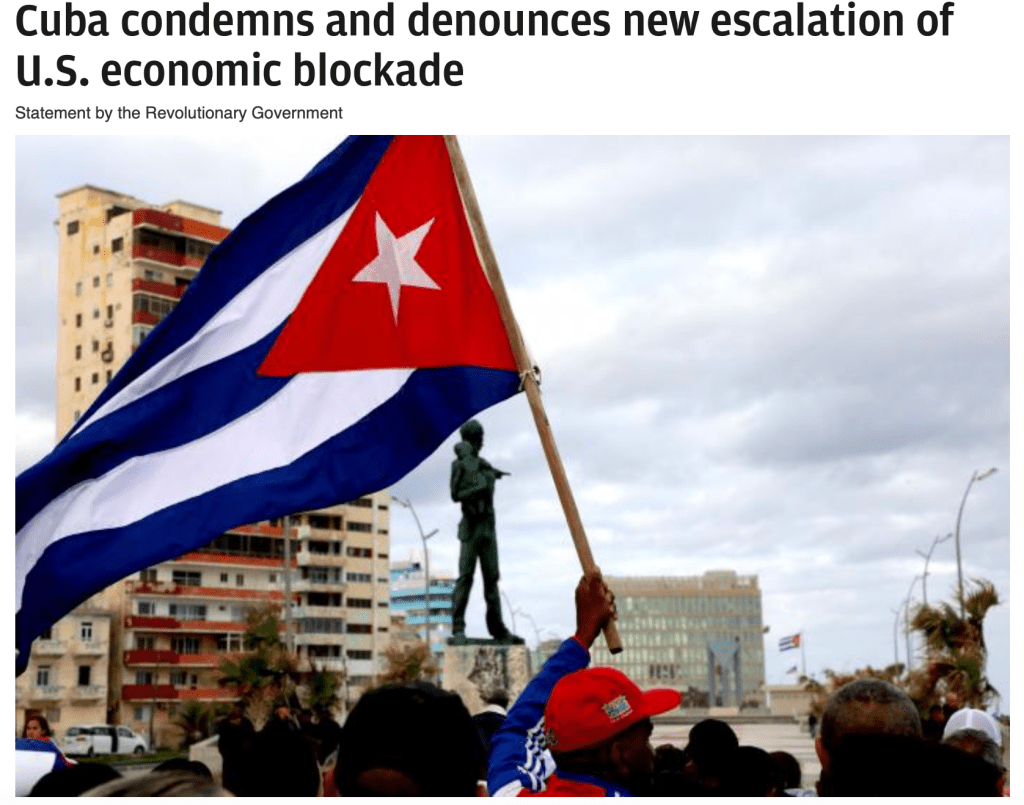

Accountability? Only to the foreign governments that have backed him: the United States, France and Canada.

In several recent public statements, U.S. authorities affirmed their support for Fils-Aimé. He is presented as the key figure capable of ensuring institutional continuity. They particularly emphasize his role in building a Haiti that is “strong, prosperous, and free.”

But it is those ships in the Port-au-Prince harbour that remind Haitians that pleasant statements barely mask the history of U.S. hard power in Haiti.

“The naval presence appears to provide the latest proof of Washington’s willingness to use the threat of force to shape politics in the Western Hemisphere,” Diego Da Rin, an analyst with the International Crisis Group, told AP News. Arrival of the ships comes during a months-long build-up of U.S. military force in the Caribbean – already used against Venezuela on Jan. 3.

An essential historical overview

Gotson Pierre, editor at AlterPresse, wrote Feb. 5 (text is translated and lightly-edited for clarity and length):

For many observers, these developments cannot be understood without a historical overview of relations between Haiti and the United States. This history is marked by repeated interventions, both military and political.

From the occupation of 1915 to 1934, with its devastating human, economic, and institutional consequences, to the [interventions in 1994 and 2004], and including the massive deployment of troops in 2010 following the earthquake, the United States has played a central role in major Haitian crises. Added to this are non-military political interventions, notably during the 2010-2011 elections, and more recently, the case of former Prime Minister Ariel Henry.

Many analysts also believe that regional bodies such as the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Organization of American States (OAS) operate within a framework heavily influenced by Washington.

Haiti maintains a complex relationship with the United States, characterized by geographical proximity, strategic interdependence, and asymmetrical power dynamics. This proximity … continues to influence the country’s political trajectory.

On the eve of February 7, 2026, amid institutional uncertainties, increased international pressure, and a reinforced military presence, the equation remains unresolved. The coming days will reveal whether these signs signal a simple continuation within established frameworks or a new phase of political realignment under strong external influence.