News reports last week said that levels of hunger in Central America have almost quadrupled in the past four years, a consequence of the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 and years of extreme climate events.

That news set me to thinking about that comforting notion that the pandemic has somehow placed us all in the same boat—and then as well to the reactions to it: we may be in the same storm, but we’re in different boats.

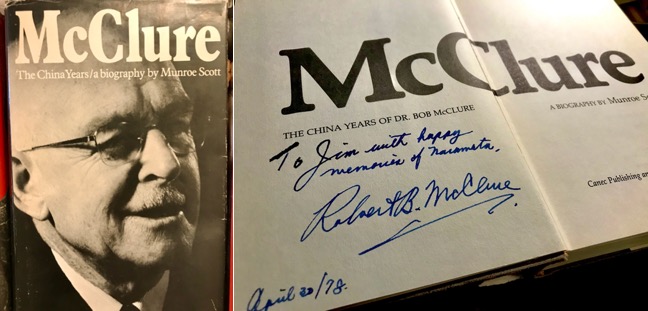

I first encountered the metaphor of a lifeboat to represent all of humanity when I was very young, perhaps 12 years old. My parents thought it was important that we hear a presentation by Dr. Robert McClure, the renowned medical missionary who was serving as Moderator of The United Church of Canada (1968-71). He was best known for his years of service in China in the decades before the triumph of the revolution in 1949, but he served after that in many parts of the world.

The auditorium of Kelowna’s First United Church was full, and we sat near the back. My memory is that Dr. McClure used the technology of the time, an overhead projector, and that one of the images was a simple line drawing of people in a boat. Most of them were at one end of the boat, and the boat looked like it was about to capsize. On the other hand, it may be that his words enabled me to make in my mind a drawing of the boat that he described. His point was about global distribution of resources. Some of us have too much; others nothing at all. It is one boat one planet: your stuff won’t save you.

Not quite a decade later, I met Dr. McClure again. We were both at the United Church’s Naramata Centre at the end of April 1978.

And, surprise, I found my notes of the event. He was in Naramata to speak at a United Church men’s conference; I was there with a very ecumenical group of about 40 youth that was attached to the Kamloops Okanagan Presbytery, and with which I stayed connected over several years during breaks from my studies in Ottawa. I had not remembered this, but my notes say that our resource person for the weekend was Gary Paterson, then the minister of the United Church congregation in Winfield, BC; decades later he too would be a Moderator. And it was Gary who introduced Dr. McClure to our group in a Saturday afternoon gathering in the upper room of a building called The Loft.

He began by “taking us” in a Concorde super-sonic jet, six-and-a-half-hours from London to Singapore. “Our world isn’t shrinking. It’s shrunk, and will continue to do so.” He spoke for about 35 minutes, and concluded: “Canada is your blessing. Now: what will you do with it?”

In between, he told us of his life in Toronto, where he lived on the 19th floor of an apartment building. He told us of the rules designed for safe living: you are not to talk to your neighbours; walk only in well-lit areas, etc.

Then he spoke of the river people of Sarawak (a Malaysian state on north coast of northern Borneo). “They live in long houses, like an apartment building turned on its side.” The long houses were divided into small apartments, side-by-side, each family having a part that was its own. “They’ve been there for 3,000 years,” he said. “They adopted this system of mutual support.” The apartments were joined together by a long, covered verandah over the river. “Neighbours are close and friends are forever.”

He offered an example. “My hospital was near the river mouth. A woman came down—a week-long journey in each direction—for a hysterectomy. I asked her, ‘Where are your children? How could you leave your children?’ ‘Oh, but doctor,’ she said, ‘we’re long-house people. The neighbours will care for them while I’m gone. Next month when my neighbour comes down, I’ll care for her children. We’re long-house people.’”

That’s mutual support. “When you’re invited to a wedding in Borneo, it’s a commitment for you too. You pledge to see that Joe and Sally will stay together, and when problems arise, you go see Joe and tell him to get his act together, and you can bet Sally will be told something by the women. One marriage in a thousand breaks down. That’s mutual support.”

He talked about the role of youth in other countries that he had visited. Read 42 years later, some of his examples of youthful collaboration seem debateable—Singapore in the years when Lee Kuan Yew exercised firm control—but the point was that governments should trust youth with more responsibility for positive social change, and that youth should take advantage of the responsibility they have now.

Twice, then, I was inspired by McClure to think of issues in their global dimensions. In subsequent years, I learned more about him and about China and about the role of Canadian missionaries there.

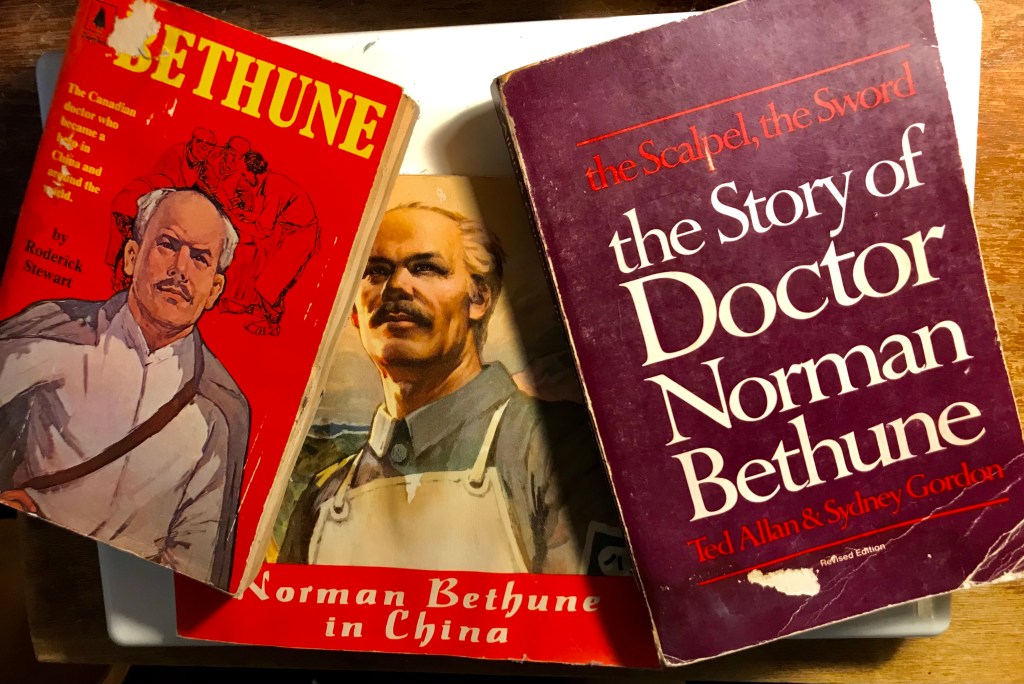

Dr. McClure is sometimes held in tension with the life and witness of Canadian supporters of the Chinese Revolution, including Rev. James Endicott, a United Church missionary, and Dr. Norman Bethune (son of a Presbyterian minister) who died in 1939 while serving as a battlefield surgeon with one of Mao Zedong’s revolutionary armies.

While I tend to the Endicott and Bethune sides of those political and theological reflections, I also celebrate McClure’s choice to live most of his life among the impoverished and marginalized peoples of the Earth, and his challenge to the rest of us to use our blessings to care for each other and the planet.

As I was putting together these notes about my memories of Dr. McClure, I was invited by a friend to see actors in a Zoom reading of a new play, China 1938, by Diane Forrest held March 8. Forrest is a writer and editor long involved in Alumnae Theatre’s new play development group and is also co-author with McClure of a 1988 volume, Vintage McClure. The play tells the story of the single encounter between McClure and Bethune in China in 1938, and is told from the perspective of the one woman who knows what happened: McClure’s widow, Amy. This play is also an inspiration, and I hope that (after the pandemic), it gets a full stage treatment.