Jim Hodgson

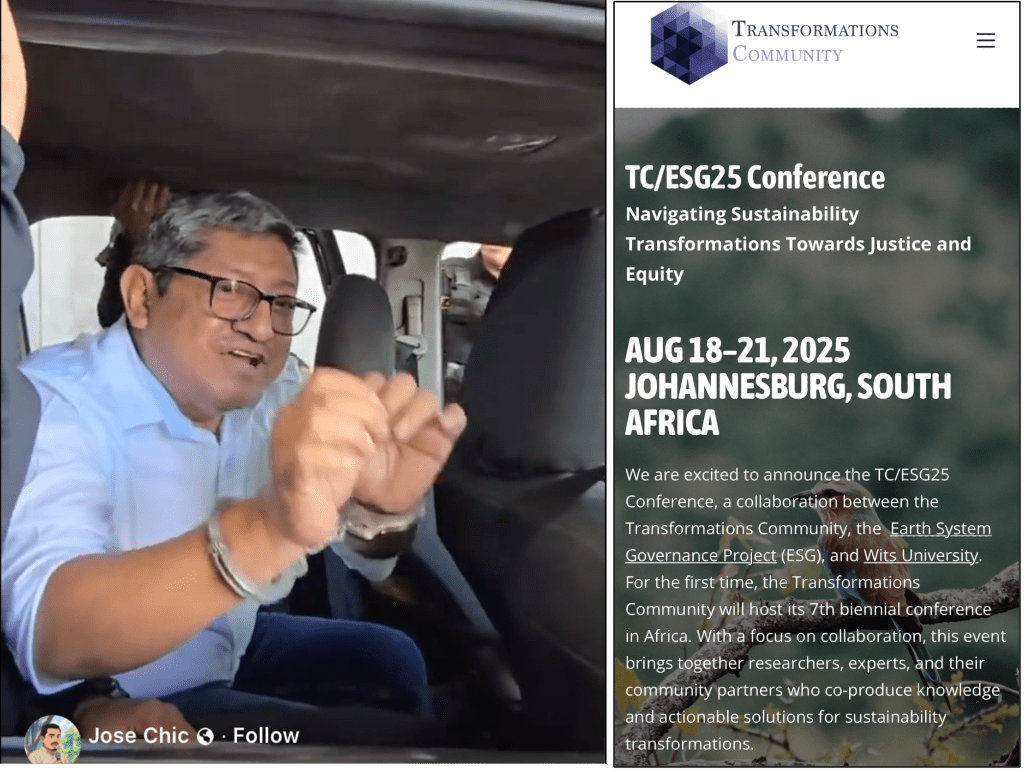

Friends and allies of Leocadio Juracán, Agrarian Reform Coordinator of the Campesino Committee of the Highlands (CCDA), are protesting his arrest Wednesday as he was about to fly to South Africa for an international conference.

“He is being criminalized for his work as a land and human rights defender,” said the Maritimes-Guatemala Breaking The Silence Network (BTS) in an urgent action request. He faces multiple charges, including aggravated trespass (usurpación agravada), directly related to his advocacy for Indigenous and farming communities across Guatemala.

(More details of the urgent action request and of Leocadio’s arrest follow below.)

I worked with Leocadio and other members of CCDA in May 2022 and March 2023, travelling with them to communities in Quiché and Izabal departments that face threats from people or companies purporting to be the true land-owners. In those communities and in scores of others across Guatemala, CCDA works with Indigenous and small-farmer communities to document their history on the land and to submit legal justification for their claims.

Leocadio and other CCDA members are known in many parts of Canada because they work with coffee farmers whose product is sent to roasters linked to Café Justicia in British Columbia and Just Us! in Atlantic Canada in a “fair trade plus” arrangement.

More details of the BTS Urgent Action request (including a template for letters in Spanish):

On August 13, Leocadio Juracán, Agrarian Reform Coordinator of the Campesino Committee of the Highlands (CCDA), was detained at La Aurora Airport as he was leaving the country to participate in a Translocal Social Movement Learning conference in South Africa.

Leocadio is being criminalized for his work as a land and human rights defender. He is currently facing multiple charges, including Aggravated Trespass (usurpación), directly related to his advocacy for Indigenous and campesino communities.

We need your immediate action:

- Private Secretariat of the Guatemalan Presidency, Ana Glenda Tager Rosado informacion@secretariaprivada.gob.gt

- Guatemalan Interior Minister Francisco Jiménez Irungaray despachoministerial@mingob.gob.gt

- Advisor to the Guatemalan Interior Minister, Claudia Samayoa ddhh3@mingob.gob.gt

With the following Canadian officials copied:

- Minister of Foreign Affairs, Anita Anand, Anita.Anand@parl.gc.ca

- Ambassador to Guatemala, Olivier Jacques, Olivier.Jacques@international.gc.ca

- Member of Parliament, Heather McPherson Heather.McPherson@parl.gc.ca

- Member of Parliament, Elizabeth May elizabeth.may@parl.gc.ca

In your message, please call on them to:

- Ensure his protection until such time as he is released.

- Follow recent UN Special Rapporteur advice to enact an immediate moratorium on evictions and grant amnesty for all criminalized land defenders.

- End criminalization of the members and leadership of Indigenous and campesino communities and organizations.

Many of these government officials are Spanish speaking. If possible, write this letter in Spanish. Otherwise, you can also send it in English.

If you’d like to send it in Spanish, you may say:

Me dirijo a usted para exigir que:

- Liberen inmediatamente a Leocadio Juracán.

- Garanticen su protección hasta el momento de su liberación.

- Sigan las recomendaciones recientes del Relator Especial de la ONU de declarar una moratoria inmediata de los desalojos forzados y de otorgar la amnistía a todos los defensores criminalizados.

- Pongan fin a la criminalización de los miembros y líderes de las comunidades y organizaciones indígenas y campesinas.

After you write this email, please share with several of your friends and contacts. Thank you so much for your urgent support to help get Leocadio Juracán free.

Leocadio Juracán, campesino leader and former congress member, arrested

Leocadio Juracán Salome, leader of the Highlands Committee of Small Farmers (CCDA), was detained Wednesday morning (Aug. 13) at La Aurora Airport in the Guatemalan capital as he was preparing to travel to South Africa for an international conference.

According to his defense attorneys, the crimes for which Juracán was arrested are aggravated trespass (usurpación agravada) and causing forest fires.

“Today, as I was preparing to travel to participate in this conference, I was arbitrarily detained at approximately 11:05 a.m. at La Aurora International Airport,” said the former congress member from the now-defunct Convergencia party.

Juracán asked his family to remain calm and told his fellow CCDA members that he is proud of their struggles “because these repressive practices by the State and corrupt officials only demonstrate that they cannot stop our just struggles with criminalization alone.”

The news of his arrest has generated expressions of solidarity from various individuals and sectors. The CCDA, the organization of which he is a member, stated that this arrest is an act of criminalization and prosecution against those who defend land, territory, and social justice and demanded his immediate release.

Representative and campesino leader

When he was elected representative for Convergencia (2015-2019), Juracán supported campesino organizations and other social sectors in their demands. In March 2017, along with then-representative Sandra Morán, he filed a preliminary lawsuit against former President Jimmy Morales in the Hogar Seguro case, which was unsuccessful.

Juracán remains one of the representatives of the CCDA, an organization dedicated to promoting rural development for Indigenous and small-farmer communities. Founded in 1982 during the military dictatorships, the organization was formally established in 1989.

Currently, CCDA supports Indigenous communities and land defenders facing issues of eviction and criminalization in several departments of the country, including El Estor, Izabal, and Cobán, Alta Verapaz. …