by Jim Hodgson

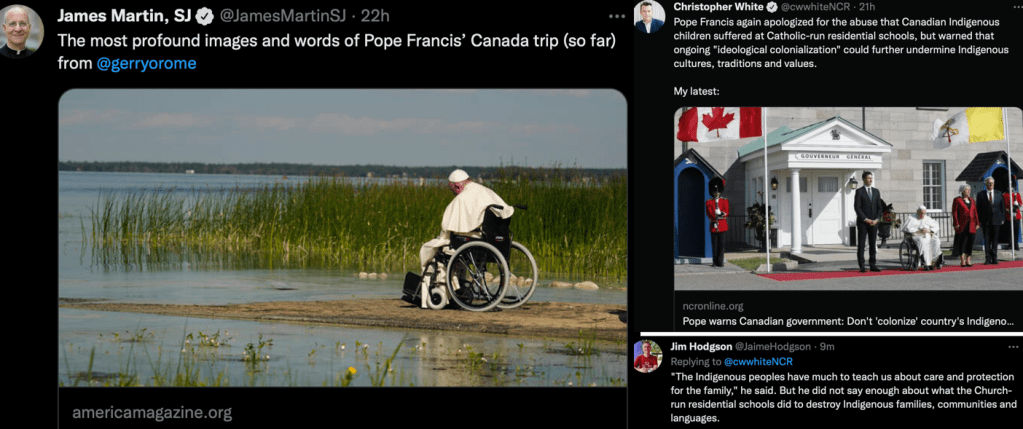

Many people who heard the apologies offered by Pope Francis in Canada were disappointed that the apologies were worded in ways that expressed regret for the actions of certain people or “local Catholic institutions” – as if religious orders like the Oblates and Jesuits are not themselves global organizations.

Building on existing teaching, the apologies offered by Pope Francis could have gone further.

As my personal penitential pilgrimage continued, I came across a forceful definition of “social sin” – relevant because of the Catholic Church’s reluctance to say something definitive, like: “the church erred,” rather than just saying, “I’m sorry.”

The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2004), in paragraph 119, describes social sin this way: “The consequences of sin perpetuate the structures of sin…. These are obstacles and conditioning that go well beyond the actions and brief life span of the individual, and interfere also in the process of the development of peoples, the delay and slow pace of which must be judged in this light.”

The entire colonial project, including the residential schools, is grotesque interference in the “development of peoples.” (That phrase echoes the name of an influential 1967 encyclical by Paul VI, Populorum Progressio, inspirational to the creation of the many Catholic development organizations an in the formation of people like your scribe.)

I was present on Oct. 12, 1984, in a sports stadium in Santo Domingo when John Paul defended the church’s role in the European conquest. Even then, his words shocked and angered me. A “black reading” of history, he said, had focused attention on the violent and exploitive aspects of the time which followed what he repeatedly called “the discovery” of the Americas.

Protest from within the church and across the hemisphere, especially from Indigenous and African-Americans, was immediate. By the time the 1992 events unfolded, John Paul came back to Santo Domingo to open a meeting of Latin American bishops (CELAM), but scaled back his participation in government-led celebrations.

He met with Indigenous and African American groups, and local media reported that he apologised. But careful reading of the texts show no apologies. To Indigenous people, he said: “There must be recognition of the abuses committed due to a lack of love on the part of some individuals who did not see their Indigenous brothers and sisters as children of God.” To African Americans, he repeated words he had used earlier in 1992 at Gorée, Senegal: “How can we forget the human lives destroyed by slavery? In all truth, this sin of man against man, of man against God, must be confessed.”

Right: I read everything I could about these debates in the mid-80s and early 90s. Part of my collection!

Pope Francis should also have addressed the “Doctrine of Discovery.” Thomas Reese, a Jesuit priest who works with the Religion News Service, wrote after the visit that the pope’s remarks in a news conference during the flight back to Rome revealed that he had not been properly briefed for the visit. Francis said he had not thought to use the term “genocide” to describe the effects of the Indian residential schools system, but agreed that it was “true.”

And he said he was confused by the phrase “doctrine of discovery.” He should have been briefed and been prepared to address the issue, persistently raised by Indigenous people because of the lasting legacy of 15th-century papal teaching. Even if those teachings were abrogated by Pope Paul III’s edict in 1537, their accumulated impact influenced U.S. and Canadian law and government policy. The TRC Call to Action 45 rejects the doctrine of discovery and calls for a new Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation to be issued by the Crown that fully honours Nation-to-Nation principles.

To be fair, the doctrine-of-discovery phrase is not used as commonly in Latin America as in North America to describe the complicity of church and state in the subjection of the Indigenous peoples of the hemisphere. It doesn’t appear, for example, in a volume edited by philosopher-historian Enrique Dussel, The Church in Latin America, 1492-1992 (Orbis, 1992) – although the various papal bulls (edicts) that gave rise to the concept are described.

In my experience, what is talked about more are impacts of colonialism, the role of the colonial state in managing Christian missions (royal patronage, power to appoint bishops, etc.), and resistance exemplified by (among others) a 1511 homily by Antonio de Montesinos to settlers in Santo Domingo (“Tell me, by what right or justice do you hold these Indians in such cruel and horrible slavery?”) or the first bishop of Chiapas, Bartolomé de Las Casas, who argued for decades on behalf of Indigenous peoples. Indeed, much of what we know about the impact of the colonialism on the original peoples of the Americas in the 16th century is from what he wrote in his History of the Indies, published in 1561. In his long life, he was able to correct errors: among them, failure to denounce the enslavement of Africans. He later advocated that all slavery be abolished.

In Dussel’s introduction, he describes “the church of the poor” as already distinct from both the colonial church and the church of the criollos (descendants of Europeans born in the Americas). “There was not a single year in the seventeenth century that did not see a rebellion of natives, blacks or mestizos….” (p.7). The criollo-led independence movements of the early nineteenth century did not advance their liberation, and resistance continues to this day.

Next: Santo Domingo in October 1992: 500 years of resistance