by Jim Hodgson

In a new document, Catholic church leaders from across the Global South blasted the “openly denialist and apathetic stance” of “so-called elites of power” in the industrialized world who pressure their governments to back away from much-needed mitigation and adaptation measures.

Preparing for the next United Nations climate change gathering, COP30, which will take place in November in Brazil, conferences of bishops from Asia, Africa and Latin America (FADM, SECAM and CELAM respectively) published a joint document entitled A call for climate justice and the common home: ecological conversion, transformation and resistance to false solutions. (You can download the document here.)

It’s the first time the three regional bodies have created a joint statement. The document offers an expansive vision for the U.N. climate conference. “At COP30, we demand that States take transformative action based on human dignity, the common good, solidarity and social justice, prioritising the most vulnerable, including our sister Mother Earth,” the bishops said.

They described the U.N. climate gathering as a moment for the church “to reaffirm its prophetic stance.”

Part of the 32-page document states:

Our demand

The climate crisis is an urgent reality, with global warming reaching 1.55°C in 2024. It is not just a technical problem: it is an existential issue of justice, dignity and care for our common home.

The science is clear: we must limit global warming to 1.5°C to avoid catastrophic effects. We must never abandon this goal. It is the Global South and future generations who are already suffering the consequences.

We reject false solutions such as ‘green’ capitalism, technocracy, the commodification of nature, and extractivism, which perpetuate exploitation and injustice.

Instead, we demand:

Equity: Rich nations must pay their ecological debt with fair climate finance without further indebting the Global South, to recover losses and damages in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania.

Justice: Promote economic degrowth and phase out fossil fuels, ending all new infrastructure and properly taxing those who have profited from them, ushering in a new era of governance that includes and prioritises the communities most affected by the climate and nature crises.

“I am raising a voice that is not mine alone, but that of the Amazonian peoples, of the martyrs of the land—we could say of the climate—and of the riverside, Indigenous, Afro-descendant, peasant and urban communities,” said Cardinal Jaime Spengler, archbishop of Porto Alegre in southern Brazil and president of CELAM. He was speaking at a news conference July 1 at the Vatican.

Vatican News reported that Canadian Cardinal Michael Czerny, prefect of the Vatican’s human development office, spoke spontaneously in the news conference to point to the document’s connection to the legacy of Pope Francis. “Ten years ago, I wonder if there is anyone who could have imagined this press conference as a fulfilment and implementation of Laudato si’. This is an extraordinary expression of what Pope Francis has called for and what Pope Leo is continuing to underline and call. I am grateful,” he said.

WCC begins Ecumenical Decade of Climate Justice Action

In Johannesburg ten days earlier, the World Council of Churches launched its Ecumenical Decade of Climate Justice Action.

During a plenary session June 21 of the WCC central committee, church leaders from six continents shared reflections and urged action for climate justice.

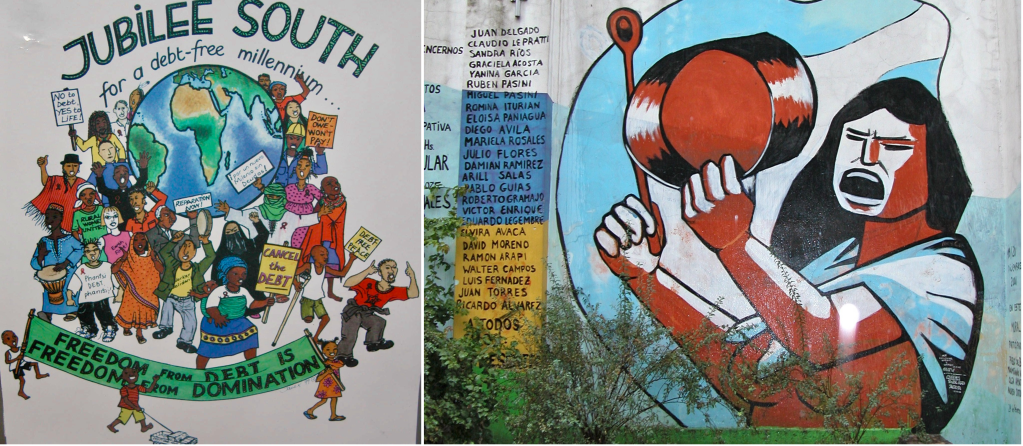

The plenary emphasized the biblical concept of jubilee as a framework for systemic transformation—a key foundation of the Ecumenical Decade. Speakers called for churches to move beyond charitable responses toward addressing root causes of climate injustice, particularly the disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities.

“Our lifestyle consumes 1.8 times what Earth can renew. Economic transformation must begin in the heart; theology must shape discipleship and discipleship must shape the world,” said Rev. Dr. Charissa Suli, president of the Uniting Church in Australia, during a theological reflection on “Jubilee for People and Earth.”

[When I shared Dr. Suli’s comment on Facebook several days ago, my colleague and friend Mark Hathaway pointed out: “In the Global North, it is more like 4.5 times what the Earth can renew—and even higher in the U.S. and Canada (I think about 6 times). The richest 10-20 per cent of humanity is responsible for most consumption and most GHGs [greenhouse gases] and a mere 100 large corporations are responsible for 70 per cent of GHGs.”

WCC has held previous ecumenical decades in the past, including The Ecumenical Decade of the Churches in Solidarity with Women (1988-1998) and The Ecumenical Decade to Overcome Violence (2001-2010).