Jim Hodgson

My background is in journalism (not theology), but I made a sort of career at the intersections of journalism, religion and Latin America. I have been close to conversations about and actions deriving from liberation theology for about 40 years. I am a follower of Jesus formed in liberation theologies that I learned alongside sugar-cane cutters, Indigenous communities, queer and trans people—folks who struggle for liberation the world over. Theirs are the stories I try to share.

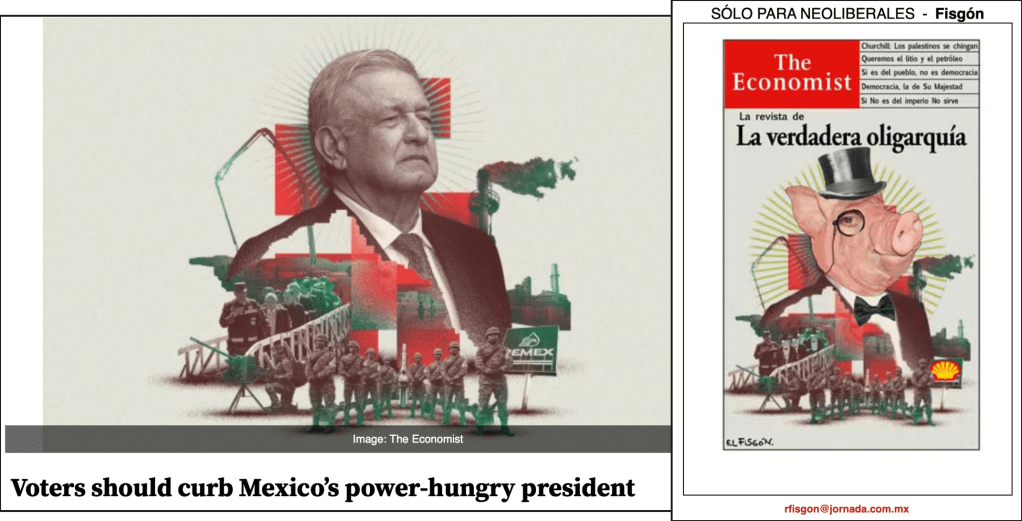

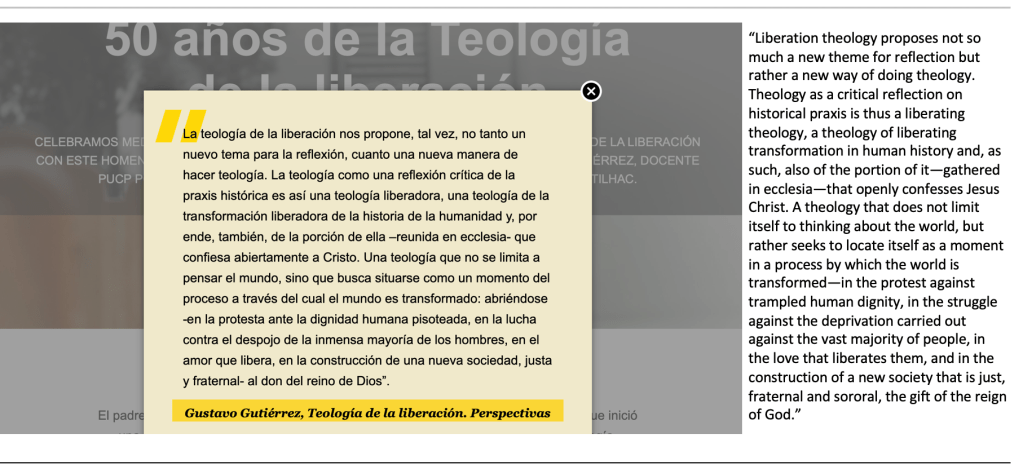

Liberation theology is a method of doing theology, not a topic, Elsa Támez has said. It begins with a situation of repression and God’s call to transform that situation. Theology then is a reflection on God’s action in history. In the mid-1980s, however, Pope John Paul II and his head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), made liberation theology a topic of heated debate. As a young journalist, I covered that debate (see the items at the bottom of this post), but over time, I concentrated more on the stories of the people who worked for change.

This year, we celebrate the publication 50 years ago of Teología de la Liberación, Perspectivas, the book that brought together a series of reflections on the practice of ministry, or the praxis of liberation, among the impoverished people of Latin America. The English translation, A Theology of Liberation (Orbis), appeared two years later. His second chapter is a critique of what was wrong with development in Latin America in the 1960s that remains valid today.

The book’s author, the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, had been sharing his perspectives in conferences since the mid-60s, including in the summer of 1967 at the Faculty of Theology at the Université de Montréal.

He was never alone in those reflections, and others were working in similar or parallel veins. The African-American theologian James H. Cone published A Black Theology of Liberation in 1970 (Orbis). In Cuba during the 1960s, Sergio Arce developed a “theology in revolution,” which was about God in human history, especially in the revolution against poverty, exclusion and imperialism. In the 1960s and 70s, priests and other people of faith organized in new ways: Priests for the Third World in Argentina, the National Organization for Social Integration (ONIS) in Peru, the Golcanda group in Colombia, Christians for Socialism in Chile during the time of Salvador Allende.

Other contextual theologies emerged—Indigenous, feminist, womanist, queer, Minjung in South Korea—along with a wide spectrum of criticism, much of it helpful in adding “new subjects” that Gutiérrez had overlooked. But sometimes, the criticism was led directly to the persecution of the “church of the poor” and to countless murders and other violations of human rights. After the assassination in San Salvador in 1989 of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter, proponents of liberation theology spoke instead of Latin American theology, a situation that persisted until the election of Pope Francis in 2013.

Bottom left: Chung Hyun Kyung, Miguel Concha.

Dussel, born in Argentina and living in Mexico, is a philosopher and historian. Támez, born in Mexico, works with the Latin American Biblical University in Costa Rica and with Indigenus biblical translators. Frei Betto is best known for exploring political implications of liberation theology, and Boff is a leading proponent of ecological perspectives in theology: they are shown during a presentation at the first World Forum on Theology and Liberation, held in days ahead of the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre in January 2005.

In ecumenical circles, Chung is remembered for sparking good debate over Christian relations with other religions during and after the Canberra Assembly of the World Council of Churches in 1993. Concha is shown during a news conference by social movements during Pope John Paul II’s visit to Mexico City in 1999. Jim Hodgson photos.

Miguel Concha, a Mexican priest of the Dominican religious order and columnist at La Jornada, wrote on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of first publication of Gutiérrez’s book:

“Liberation theology is not limited to helping the poor individually. Nor is it reformist, trying to improve a situation but leaving intact the types of social relations and basic structures of an unjust society. Beyond moving ethically in the face of collective misery, it considers impoverished people to be subjects of their own liberation, valuing in them their awareness of their rights and capacity for resistance, organization and transformation of their situation.”

In these 50 years, I think the formal presentation of Gutiérrez’s method has become melded in our imaginations with other processes:

- the outcomes of the II Vatican Council and several meetings of Latin American bishops (CELAM), especially the articulation of the church’s “preferential option for the poor” at the CELAM conferences in Medellín in 1968 and in Puebla in 1979;

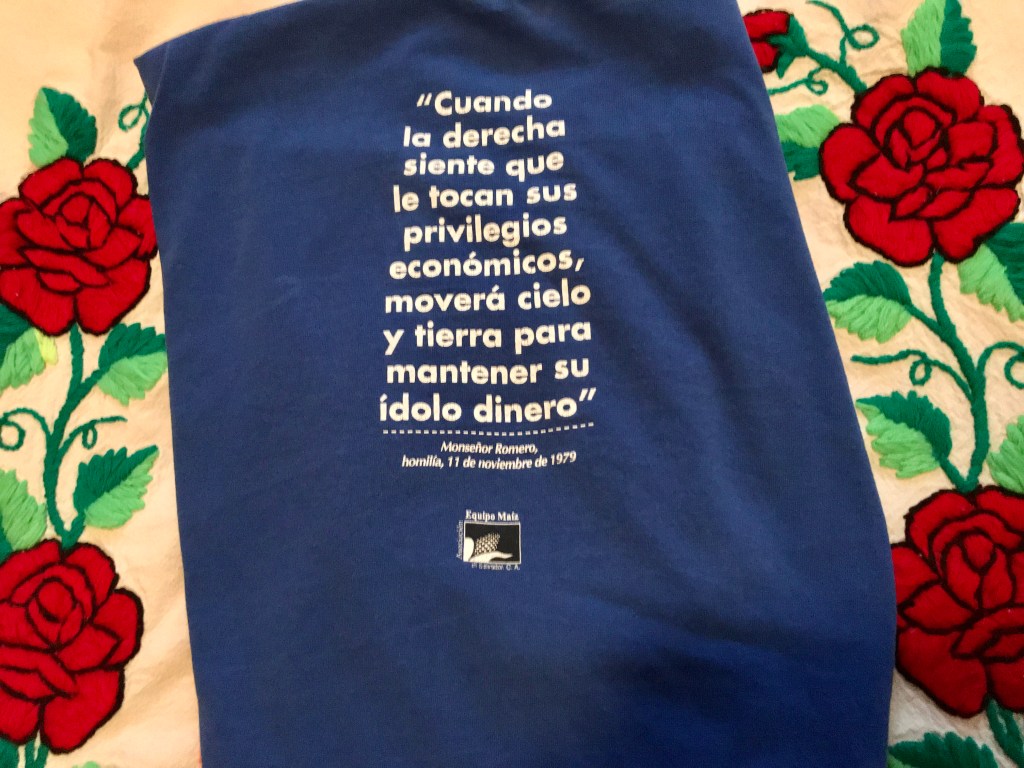

- the pastoral action of certain church leaders (Sergio Mendes Arceo, Hélder Câmara, Oscar Romero, Samuel Ruíz, the Argentinean Methodist Federico Pagura, among many others), whether they identified explicitly with liberation theology or not;

- a mix of popular education and base Christian community experiences; and the political action of movements like the Sandinista Front In Nicaragua in the 70s and 80s, or that which propelled Jean-Bertrand Aristide to the presidency of Haiti in 1990 and again in 2000.

During the last week of October, Fr. Gustavo, now 93 years of age, joined with scores of scholars and faithful for an online seminar to mark the anniversary. Videos of the presentations can be viewed (in Spanish) on the Facebook site of the Instituto Bartolomé de Las Casas.

I am appending here below parts of some to the articles I wrote in the mid-80s about the debates over liberation theology.