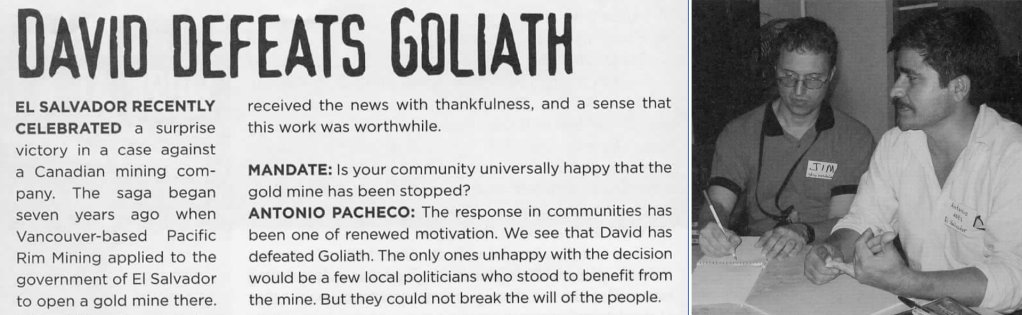

by Jim Hodgson

The global allies that united to accompany communities in El Salvador in their defence of water resources against a Canadian mining company are working together again to defend five community leaders and to ensure that a national ban on open-pit mining stays in place.

Thursday, Jan. 11 marks one year since Antonio Pacheco and four colleagues were arrested in and near Santa Marta in northern Cabañas.

On Jan. 5, 185 academics and lawyers, and 13 organizations from 21 countries sent an open letter to the Salvadoran Attorney General calling for the case against the five to be dropped.

The five water defenders were FMLN combatants during the 1980-1992 civil war in El Salvador and are protected, the lawyers argue, by El Salvador’s internationally-recognized Peace Agreement and the National Reconciliation Law, both signed in 1992.

The lawyers’ letter says that Salvadoran prosecutors lack evidence, but the men – released from jail in September – still face charges of murder, unlawful deprivation of liberty, and unlawful association, alleged crimes that took place 33 years ago within the context of the civil war.

Water protectors in El Salvador say the arrests are politically motivated and a strategy to demobilize strong community opposition to mining as the government of President Nayib Bukele seeks to end the 2017 national prohibition of metals mining.

“The selective violation of the National Reconciliation Law to muzzle key leaders of the anti-mining movement while stifling any meaningful attempt to bring the largest perpetrators of human rights violations during the civil war – the Salvadoran military – to justice is a telling sign of the political motivations behind this case,” says the lawyers’ letter.

The perpetrators of the largest massacres of the civil war and of several high-profile assassinations have never been prosecuted in El Salvador. A series of massacres in northern Cabañas in late 1980 and in 1981 that led the people of Santa Marta and nearby communities to flee across the Lempa River into a six-year exile in Honduras have scarcely been investigated.

Late last year, an international delegation visited Santa Marta and other parts of El Salvador to look more deeply at the charges against the Santa Marta Five and the broader context of human rights violations in El Salvador. Their report “State of Deception: Fact Finding Report on the Detained Santa Marta Water Defenders, Mining, and the State of Human Rights under the Bukele Administration, will be released Thursday, Jan. 11.

The report will show how Bukele has – in the words of Manuel Perez-Rocha of the Institute for Policy Studies – “reduced the independence of the judiciary, violated basic human rights, suspended civil liberties, and upended the rule of law.”

Human rights groups including Amnesty International have documented severe abuses of human rights under the guise of overcoming street-gang violence. Says Amnesty: “As of October 2023, local victims movements and human rights organizations had recorded more than 73,800 detentions, 327 cases of forced disappearances, approximately 102,000 people imprisoned – making El Salvador the country with the world’s highest incarceration rate – a rate of prison overcrowding of approximately 236%, and more than 190 deaths in state custody.”

Among the most recently-targeted is Rubén Zamora, the 81-year-old former politician and diplomat who was, for many, the public face of the coalition of groups aligned against the government during the civil war. Zamora was a Christian Democrat who left his party in 1980 over its alliance with the armed forces. He was a member of congress in the early 90s, and ran for the FMLN as its presidential candidate in 2004.

Absurdly, he is accused of helping to cover up one of the high-profile massacres – El Mozote in 1981, when about 1,000 people were murdered, the largest single massacre of civilians in modern Latin American history – by being a member of congress when the abysmal 1993 amnesty law was approved. But Zamora opposed that law and refused to add his signature to it once it was approved by other legislators. (That law was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2016.)

ADES and other Cabañas organizations that support the Santa Marta Five have also called for support to Zamora. There is also an on-line petition that you can sign.