They’ve been gone for almost 10 years now, those 43 education students who were taken one night in Iguala, Guerrero. Hypotheses abound but despite promises and investigations, the crime is not solved.

But there are new revelations about the cover-up orchestrated at the highest levels of the Mexican state in weeks after the disappearance (see below).

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known popularly as AMLO) has done many good things as he nears completion of his six-year term. But his failure to press finally for the full truth of the Mexican army’s involvement in the disappearance of the students who attended the Ayotzinapa teachers training school stains his record.

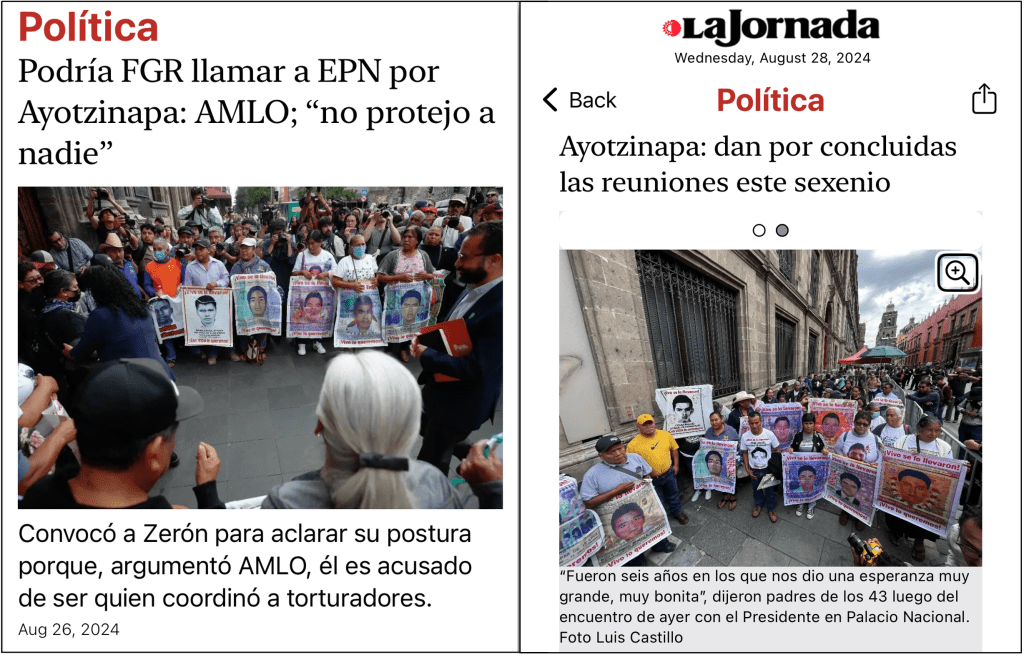

During a march in Mexico City on Monday, Aug. 27, Luz María Telumbre, mother of one of the disappeared students, told a reporter that she would be among the parents who would meet the president again the following day. This time, she said, it will be to say: “’thanks for nothing’ because we’re still walking, shouting in the streets for justice and truth.”

Another mother, Joaquína García, said “it isn’t fair that we should be in the streets for 10 years seeking justice and we still don’t know anything about the boys.” She added that she wants to tell the next president, Claudia Sheinbaum, “that we will not stop struggling until we find them and that as a woman and mother, we hope she will understand us.”

On the night of Sept. 26, 2014, students from the Ayotzinapa Normal School were attacked in Iguala, Guerrero, after they had commandeered buses to travel onward to Mexico City for a protest over the Oct. 2, 1968, massacre of student protesters at Tlatelolco plaza in Mexico City.

In Iguala, six people—including three students—were killed in the assault, 25 were injured and 43 students were abducted and presumably murdered later. Leading suspects are members of the Mexican army who worked alongside municipal officials and drug-traffickers who were trying to move opium gum (semi-processed heroin) on one of the buses that was taken.

What happened before?

One afternoon in the late 1990s, I accompanied a group of students from Canada and the United States to a meeting with rural teachers in the mountains near Tlapa in northeast Guerrero.

These teachers spoke for communities afflicted by poverty, military incursions and the drug war. They taught their students in Spanish as well as in Nahuatl or one of the other Indigenous languages spoken in the area. They dedicated their lives to strengthening rural communities through the education of children. They were convinced that people needed to be able to organize themselves and demand that their rights be respected so that things would begin to change.

“The rural teachers colleges are among the only means of social mobility within the reach of young people from campesino communities,” wrote Luis Hernández Navarro, opinion editor at La Jornada, back in 2011. “Through them, they have access to education, housing, food and later, with luck, a job they are qualified to do.”

The first time I that I can recall hearing of the Ayotzinapa school was in January 2008, when Blanche Petrich, another La Jornada journalist, came to Toronto to support work by Canadian churches in defense of refugees from Mexico. She told us:

“To describe the panorama of repression in Guerrero, it’s enough to follow the route of the popular movement. ‘Wherever there is organization, protest, defense of human rights, mobilization of roadblocks, there is repression, irregular apprehensions and arrest warrants,’ we’re told by the [Tlachinollan] human rights organization in the La Montaña area, led by Abel Barrera. That is, the campesinos who oppose the taking of their lands for a dam in La Perota, close to Acapulco, the ecologists who resist cutting of trees in the Petatlán sierra, the laid-off workers of a government office in the state capital of Chipalcingo, the community leaders of Xochistlaguaca, the students at the normal school in Ayotzinapa: they all suffer persecution.”

And what’s new?

Through an access to information request, journalists obtained new information about the cover-up that was orchestrated after the abductions by high ranking authorities in the government during meetings presided over by then-President Enrique Peña Nieto and attended by then-Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam and other officials. Their “historic truth” version—since proven false—contended that local police turned the students over to a drug gang which murdered them, burned the bodies at a garbage dump, and put the remains into a river.

Tomás Zerón, former head of investigations for Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office, is now a fugitive hiding in Israel, beyond the reach of the Mexican justice system. But in 2022, he answered questions posed in writing by Alejandro Encinas, then Mexico’s Interior Undersecretary for Human Rights.

Appointed by AMLO’s government, Encinas chaired the Commission for Truth and Access to Justice in the Ayotzinapa Case (COVAJ). The commission included family members and their advisors. Their report, published in August 2022, said federal, state and municipal politicians, along with the armed forces and local police, knew what had happened.

But that report and a subsequent one in September 2023 have been undermined by the refusal of President López Obrador to accept its conclusions and his accusations against the human rights groups that accompany the families, including Tlachinollan and the Jesuit-backed Miguel Augustín Pro Human Rights Centre.

After a meeting Tuesday (Aug. 27) with the president, the parents said it was the last one they would hold with him before he leaves office Oct. 1.

“We ended badly,” said their lawyer, Vidulfo Rosales of Tlachinollan. He added that while in the first three years of this government, they saw clear good will to get to the truth, in 2022, the situation changed. “This is when we touched the sensitive fibres of the Mexican Army; we could advance no further. There was a break, a crisis, including in the relationship, the dialogue.”

“This government, unfortunately, could not give us truth and justice,” he added.