by Jim Hodgson

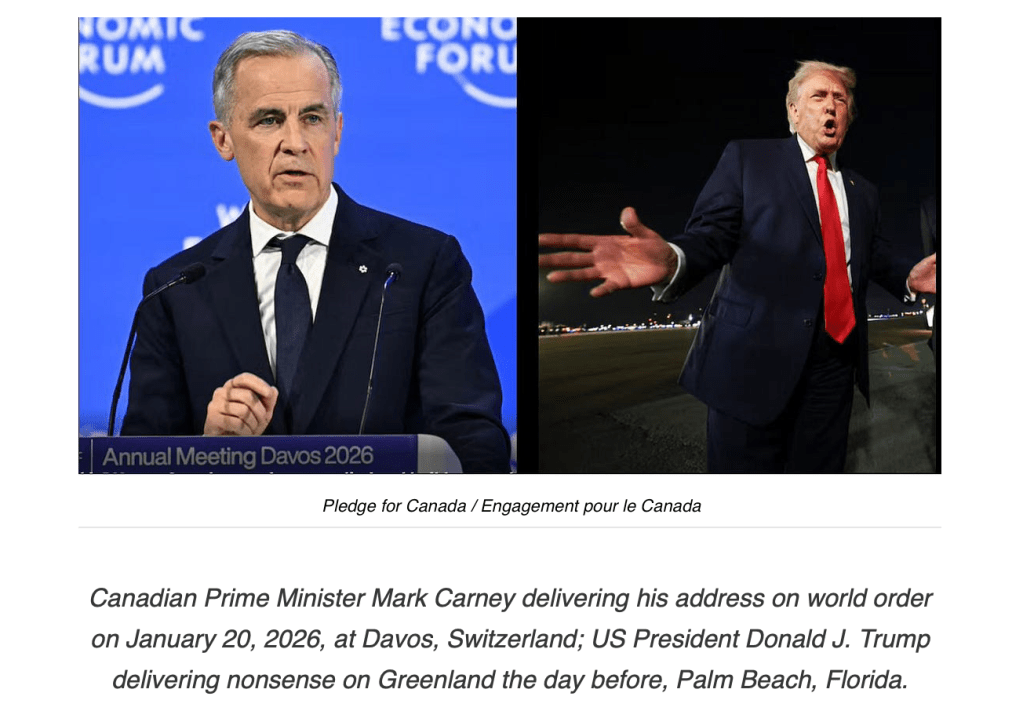

It was too much to hope that the well-heeled audience at Davos would boo Donald Trump from the stage a day after they had offered Mark Carney a standing ovation. But by the end of Wednesday, it seemed that the wall of resistance to any U.S. take-over of Greenland was successful, and the president backed down. An important victory.

Still, “la rupture de l’ordre mondial” of which Carney spoke remains. And he’s right: we shouldn’t mourn it. The international financial institutions invented in 1944 at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, gave overwhelming power to the rich countries of the Global North.

And the United Nations system that followed, with a veto given to each of the five most powerful countries, has protected their interests – even in the face of overwhelming contrarian votes in the UN General Assembly. Think, for example, of the annual vote to end the cruel U.S. blockade of Cuba.

That order was designed by the nations that existed at the end of World War II, especially the colonial or neo-colonial states of Europe and the Americas. Most of the Caribbean, Africa and large parts of south Asia were still under colonial rule. That order imposed and perpetuated a Global North-based order on all the new nations that were born in the 25 years or so after the war: the majority of nations that exist today.

And that order, at least in the eyes of three of the five veto-holders, effectively imposed capitalism as a synonym for democracy. The United States and its allies were satisfied with a sort of formal democracy, a certain alternance between parties of the right and centre-right, and if that failed, then a military government was a useful interlude until the real order could be re-established and markets were safe.

Canada would “go along to get along,” as Carney admitted.

Just as it did less than three weeks ago when the United States bombed Venezuela and kidnapped its president. And just as it has for more than two years over Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

In his speech, Carney seemed to offer a vision of capitalism without the now-erratic United States. It’s still reliant on resource extraction, military spending, and massive capital investment.

But if we are all to grow and thrive, we must demand more. We require an end to practices that exploit social inequities and our shared ecology.

Alternatives

Because of the paths on which my life has taken me, one that is especially close to my heart is the call from the Indigenous people of Zapatista communities in southern Mexico for “a world with room for all” – “un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos.” But other visions come from other places, including three decades of gatherings of the World Social Forum.

More than 50 years ago, the majority world united behind a vision of economic decolonization, sovereign development, and international cooperation across areas such as debt, trade, finance, and technology. That vision became known as the New International Economic Order (NIEO) and was adopted by the UN General Assembly. But, power relations being what they are, it was never implemented. (Progressive International put together a set of reflections that trace its history and update the proposals for the 21st century.)

In March last year, the World Council of Churches and several global communions of churches repeated their call for a New International Financial and Economic Architecture (NIFEA). “It is immoral that over a billion people – half of them children – subsist in poverty whilst billionaires increased their wealth by over 15% in 2024 to US$15 trillion. It is outrageous that the richest 10% of the global population receives more than half of global income, whereas the poorest half earns merely 8.5% of it,” they said in a statement.

They expressed deep concern about “a rapidly escalating climate and biodiversity emergency that jeopardises livelihoods and poses an existential threat to all life.” It notes that “several tipping points are close to being crossed or have already been crossed, leading us to recognise that we may be beyond a point of no return.”

The old order is dead. The time in which we are living demands we do better.