by Jim Hodgson

A decade ago this week came news that the United States and Cuba would begin a process to restore relations broken in 1961 in the wake of the Cuban Revolution and at the height of the Cold War.

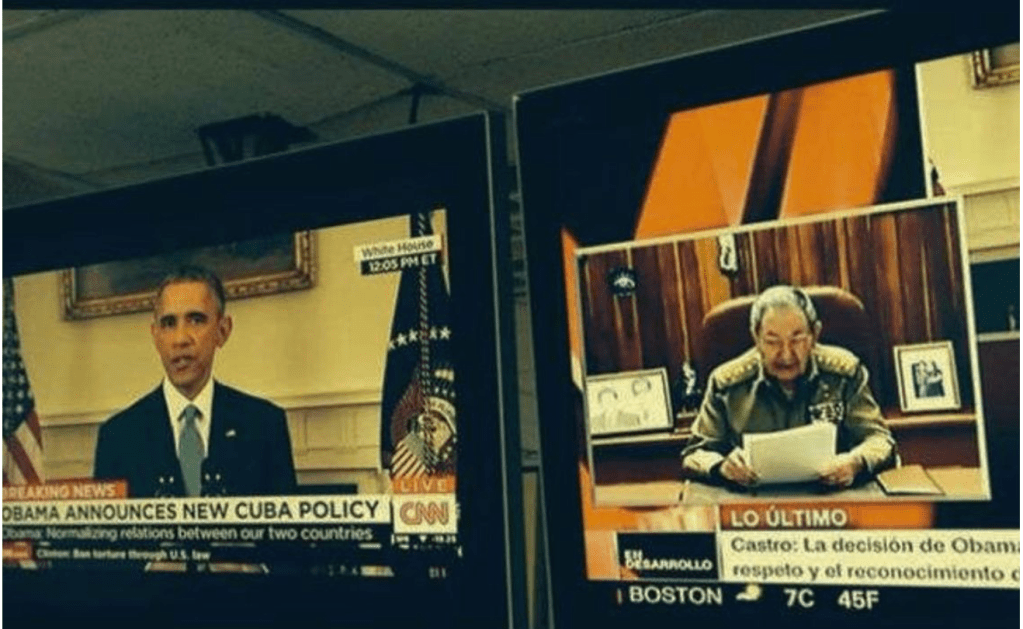

“Today, America chooses to cut loose the shackles of the past so as to reach for a better future—for the Cuban people, for the American people, for our entire hemisphere, and for the world,” said President Barack Obama.

“As we have repeated, we must learn the art of coexisting, in a civilized manner, with our differences,” said President Raúl Castro.

Obama did not, however, back away from historic U.S. criticisms of Cuba’s revolutionary option; nor did Castro promise to surrender national sovereignty or its political system. But a process was set in place for dialogue over differences. Prisoners were released on both sides of the Straits of Florida. People could visit each other once again. Perhaps the United States would finally become a “good neighbour” to Cuba and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Tragically, hope inspired that week and by Obama’s visit to Havana in March 2016 has proved but fleeting—“ephemeral” says an editorial Tuesday in Mexico’s La Jornada daily newspaper.

When Donald Trump came to power in January 2017, he cancelled all the advances of the Obama era and, as La Jornada puts it, added “new layers of sadism to the criminal blockade against Cuba.” He even maintained his “maximum pressure” on Cuba during the COVID-19 pandemic, obstructing Cuba’s efforts to obtain vital medical supplies during the crisis. (Yes, Cuba produced its own vaccines, but syringes and other specific items were in short supply.)

We kind of knew then (as we do now) that dealing with Trump in a rational manner would be difficult, but it was a disappointment that President Joe Biden failed so miserably to alter any but the most minor of sanctions that the United States—alone in the world—applies to Cuba. The harshest measure—maintaining Cuba on a U.S. list of “state sponsors of terrorism”—blocks Cuba from normal international financial activity. It is applied in an “extraterritorial” way, complicating efforts even by humanitarian organizations in other countries (including Canada) to share financial resources or for freight companies to carry material aid to Cuba.

As I have said before, sanctions in almost every instance harm civilian populations and fail to produce their stated goal: regime change. In Cuba today, the consequences verge on catastrophic (again, the word used by La Jornada): Cuba is now “unable to generate urgent resources in order to restore its energy system, start food production, take advantage of its tourism potential, and restore industries devastated by the isolation to which Washington has subjected it.”

In these next four years, leaders of the United States represent a menace to their own population—especially Trans people, pregnant women, and immigrants—but also to other nations. In the face of Trump’s tariff threats, Canada and Mexico are both scrambling to mitigate damage. They’ll be choosing which battles to fight.

Canada, together with countries like Mexico, must retain its distinct foreign policy, a feature of which for 65 years has been solidarity with Cuba. And those of us who care for Cuba’s choice to do things differently must remind Trump and his cohort that they cannot punish a country simply because it chooses not to govern itself as the United States wishes.

2 thoughts on “Cuba-U.S. relations: the thaw that didn’t happen”