by Jim Hodgson

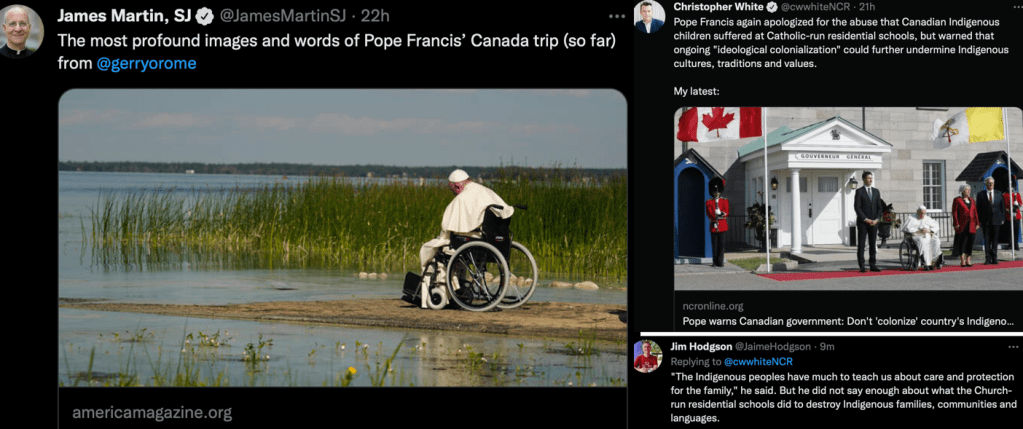

Through the six days of the pope’s “Penitential Pilgrimage,” I mostly refrained from comment about the visit. It was best, I felt, that people hear the voices of residential school survivors and other Indigenous people, along with the voice of Pope Francis. I made my own penitential pilgrimage, albeit without travelling far. I am humbled as always by the voices of survivors and their families.

Folks who know me know that I have deep roots in two churches: the Roman Catholic Church and The United Church of Canada. As time goes on, I feel ever more disinclined to choose between them. I stand among them with others as an ecumenical Christian, and among other believers and all people of good will as we discern good ways forward together.

Here begins a three-part series of reflections (accompanied by many links to other articles and documents) from my virtual pilgrimage. Some of what follows is drawn from events of those late July days and other parts come from my reporting of four of Pope John Paul II’s visits (Canada in 1984, the Dominican Republic in 1984 and 1992, and Mexico in 1999), as well as my life as a pilgrim working and travelling between Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean since 1983.

In my nomadic childhood (which involved sojourns in three provinces before I was four and in yet another after I turned ten), we would occasionally visit relatives in Wetaskwin and Camrose, driving north on Highway 2A through Maskwacis – known in those days to us settler folk as Hobbema. This was in the 1960s and early 70s, and we hadn’t a clue about the Ermineskin Indian Residential School (ERS) that operated there from 1895 to 1975.

I began my virtual pilgrimage by learning more about the school. Many students were from the Ermineskin Cree Nation, and students came as well from the other three Maskwacis bands: Samson Cree Nation, Louis Bull Tribe and Montana First Nation – and from farther away too. ERS was one of the largest residential schools in Canada. In 1956, enrolment peaked at 263 students.

It was begun by two religious communities: the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) and the Sisters of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin (SASV). The sisters left in 1934, and the Oblates gave up management of the school in 1955 and of the student residence in 1969 when the federal government took over the entire complex.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has compiled stories of what went on there.

I was blessed to attend the presentation in Ottawa in 2015 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report and Calls to Action, and so I knew from the stories of survivors that days would come when stories would be believed, truth emerge, and cemeteries uncovered.

On May 28, 2021, the report came that 215 graves of children had been found on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School. I knew two men, leaders respectively in the Syilx and Nlaka’pamux nations, who survived their attendance at that school and who guided me in the late 1970s into good ways of listening to Indigenous peoples and hearing their stories.

One of the leaders whose words seemed to press my conscience was Natan Obed, the leader of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami – the political organization that represents 65,000 Inuit people across Inuit Nunangat (lands and waters in regions known as the Nunavut territory, Nunavik in northern Québec, Nunatsiavut in Labrador, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in NWT). In a conversation with Tanya Talaga, he said, “I may have been naive to think that the institution could come here and apologize in the fullest capacity it possibly can, without the accompanying religious element that ultimately is at odds with the very purpose of the visit.” (I was disappointed that the pope did not immerse himself more fully in Indigenous ceremony; instead, Indigenous people were again immersed in Catholic ceremony. I was appalled by the use of Latin in the mass at the Commonwealth Stadium: a friend said it seemed like conservatives in the church had set out to “sabotage” the pope’s visit.)

After hearing the apology in Maskwacis, Obed told a television reporter that one of the challenges for Indigenous people has been precisely where to seek justice among the religious orders and congregations, bishops and their dioceses, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), and the Vatican.

I understand that from outside the Catholic Church, it looks monolithic and pyramidal. And as you contend with it, you come to understand that a variety of perspectives and relative levels of autonomy co-exist among the “Catholic entities” (the phrase used during the residential schools settlement negotiations among churches and government). According to the CCCB, about 16 of 70 Catholic dioceses, as well as three dozen Catholic religious communities, were associated with residential schools.

This has resulted in several different apologies from the Catholic entities (dating back to 1991) and diverse responses to demands for release of documents. This is also why it was necessary for the pope, who represents the unity of the church, to apologise here. (Apologies from other churches and governments are listed here.)

Next: The church, systemic injustice, social sin and the “doctrine of discovery”