The murders last month in the Sierra Tarahumara of Mexico’s Chihuahua state of two Jesuit priests sparked grief and tension among Indigenous people, the Catholic church and various levels of Mexican government. The priests were Javier Campos Morales, 79, and Joaquín Mora Salazar, 81, known respectively as Gallo and Morita. A third person killed with them, Pedro Heliodoro Palma, was described as a tourist guide. Their bodies were taken by the killers, who were said by police to be linked to the Sinaloa cartel.

Mexican Jesuits recognized “with humility” that in a country with more than 100,000 disappeared people, they were fortunate to recover the bodies of their brothers within 72 hours of their disappearance. “A search that was coordinated among three levels of government reflects intense attention and action are likely not accessible to the immense majority of families whose cases do not gain public attention.”

In the last 30 years, 70 Catholic priests have been murdered in Mexico, including seven during the current presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO). The motives, wrote sociologist Bernardo Barranco in La Jornada, are multiple: theft, kidnapping, extorsion, passion and politics. I would add incidental contact with drug-traffickers who, in this case, seem to have been chasing someone who sought refuge in the church in Cerocahui, municipality of Urique, where the Jesuits have carried out ministry among the Rarámuri Indigenous people in the Sierra Tarahumara.

In 2006, then-President Felipe Calderón launched a military-led offensive against the drug cartels in an attempt to curb their violent turf wars. Instead, the violence became worse.

In the town of Creel, in southwest Chihuahua, on Aug. 16, 2008, gunmen opened fire on a group of young people who were participating in a barefoot family race. One of them was carrying his baby in his arms. Some of the youth were related to the town’s mayor but had no link to organized crime. Thirteen people, including the baby, died.

A few weeks later, Jesuit Fr. Ricardo Robles wrote:

For a while now, but especially in recent months, a group of friends and I have been trying to better understand the significance of the evermore extended presence of the narco in the Sierra Tarahumara. It’s the narco-planting, that in some areas has seen four generations of narco-cultivators and has made this way of life become ordinary, indeed almost the only lifestyle now. But it is also the narco-transportation, the narco-struggle for control of territories, the generalized narco-corruption, including paid-for narco-elections, the abundant narco-money-launderers and the small narco-traffickers and narco-consumers.

What is new in what we are seeing with the narco? A Rarámuri friend said it is the same thing they have seen for five centuries. “It’s another activity in which Indigenous people are pressured and obliged to work. It was the same with the mines,” he said. “There was the same violence and crime, the same deaths, the same enrichment and impoverishment and in everything we were left with the worst part. The same with the invasion of our territories, the same with the theft of our forests, the same with tourism that even takes our water, the same with the return of the mines. The same when one day they brought the planting of marijuana and poppies. For us it’s the same thing. This is how invasions are, but perhaps for you this seems new.”

Perhaps all that is truly new is that now the blood is spattered on all of us, that we are all being conquered, tyrannized and forced to submit.

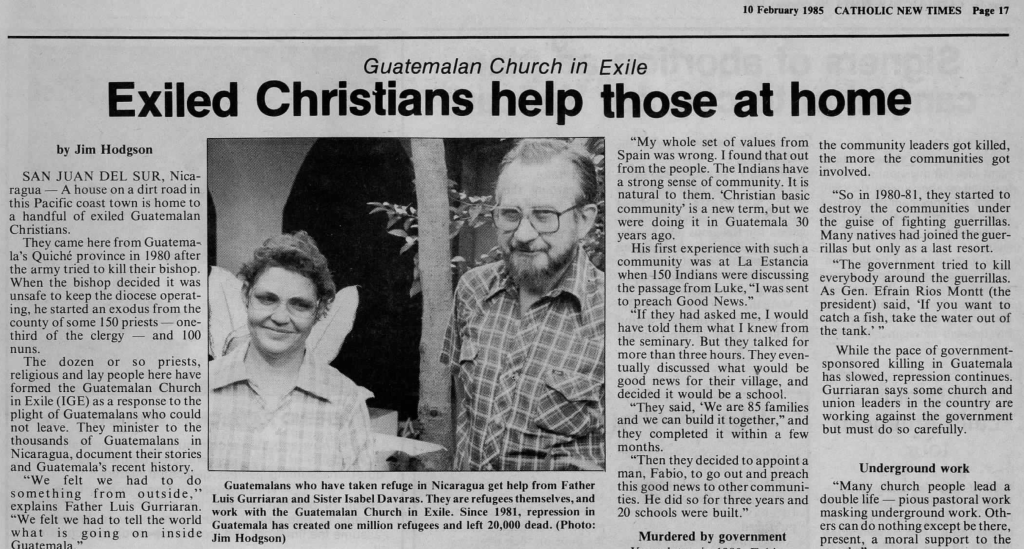

The Spanish conquistadores, hungry for gold and other precious minerals, arrived in the Rarámuri territory in 1589. The Jesuit religious order followed in 1608. They were expelled from the Spanish colony and 19th-century Mexico, but returned after 133 years in 1900 with the intention of educating the Indigenous people. La Jornada journalist Luis Hernández Navarro writes that after facing about 40 years of resistance, the Mexican Jesuits finally began to learn from the Rarámuri. By the 1960s, they had set aside their western notions and moved closer to the Rarámuri cosmovision. The Rarámuri converted the Jesuits “from being carriers of a doctrine into disciples, from being do-gooders into friends of the men and women of the Sierra Tarahumara, and companions in their secular resistance and defence of their freedom and autonomy.” Hernández adds that the two Jesuits killed in June had “accompanied the Rarámuri people who were subjects of their own history and not objects for colonization.”

At the funeral June 25 of the slain priests, Fr. Javier Ávila Aguirre, the Jesuit who serves at Creel, called on President López Obrador during his homily to look again at his approach to public security. “Our tone is peaceful but loud and clear. We call for actions from government that end impunity. Thousands of people in pain and without voice clamour for justice in our nation. Hugs are no longer enough to cover the bullets.”

In his daily news conference on June 30, the president responded: “Those expressions of ‘hugs are not enough.’ What would the priests have us do? That we resolve problems with violence? That we disappear everyone? That we bet on war?”

The point, however, made by human rights groups and some religious leaders, is that after nearly four years AMLO’s approach to the drug war has not produced a noticable reduction in violent attacks on civilians – or priests or journalists. While the president says he is working on the “causes of violence” – poverty, marginalization, exclusion – what people want is protection now.

The issues raised by the Jesuits and human rights groups should not be seen as normal political attacks on an incumbent politician, but rather contributions in a search for real solutions.

Bernardo Barranco, the sociologist-columnist cited above, told a La Jornada colleague in an interview that churches are present in places where the state is absent, and that they could have a mediating role. He pointed to the state of Guerrero where, for example, Bishop Salvador Rangel of Chilpancingo-Chilapa negotiated in 2018 with organized crime so as to end the assassination of local candidates and to permit the population to vote.

Such conversations may not lead to solutions in every instance, but it’s clear that new ideas and less defensive dialogue are needed if Mexico is to find a way forward.

And North American narco-consumers need to say NO to illegal drugs, at least for the sake of solidarity with victims of narco-violence.