by Jim Hodgson

In the face of U.S. President Donald Trump’s threats to impose new tariffs on any nation that exports oil to Cuba, we all need to stand firm. Here are two ways to send messages to Canadian leaders.

First, the Take Action proposed by Canadian churches, trade unions and NGOs. Yes: it pre-dates the current crisis, but its message is vital. Canada cannot be silent.

Second, the Canadian Network on Cuba has an on-line petition to Canadian parliamentarians. It too pre-dates the immediate crisis, but is still an important means to communicate.

Of course you can write your own letters to leaders in whichever country you live.

Take heart from increasingly strong messages from Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum.

Today, she denied Trump’s claim a night earlier that they had talked about Cuba, much less that he had asked her to stop sending Mexican oil to Cuba and that she would comply.

The only such conversation, she said while travelling in Sonora state, had been between her foreign affairs secretary, Juan Ramón de la Fuente, and U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Sheinbaum has said several times this week that her country will continue to send humanitarian aid including oil to Cuba. Various sources report that Cuba has only enough oil to satisfy needs for another 15 to 20 days.

For his part, de la Fuente told Mexican legislators today that Mexico considers it “unacceptable that there not be humanitarian aid where it is needed, when some country in the world requires it.”

Saturday night, while travelling from Washington DC to his home in Florida, Trump said the United States was beginning to talk with Cuban leaders. (There is no confirmation as of Sunday evening from Cuba that such talks have begun.)

In comments to reports on Air Force One, he added: “It doesn’t have to be a humanitarian crisis. I think they probably would come to us and want to make a deal,” Trump said Saturday. “So Cuba would be free again.”

He predicted they would make some sort of deal with Cuba and said, “I think, you know, we’ll be kind.” (U.S. interventions since 1812 have not been known for their kindness.)

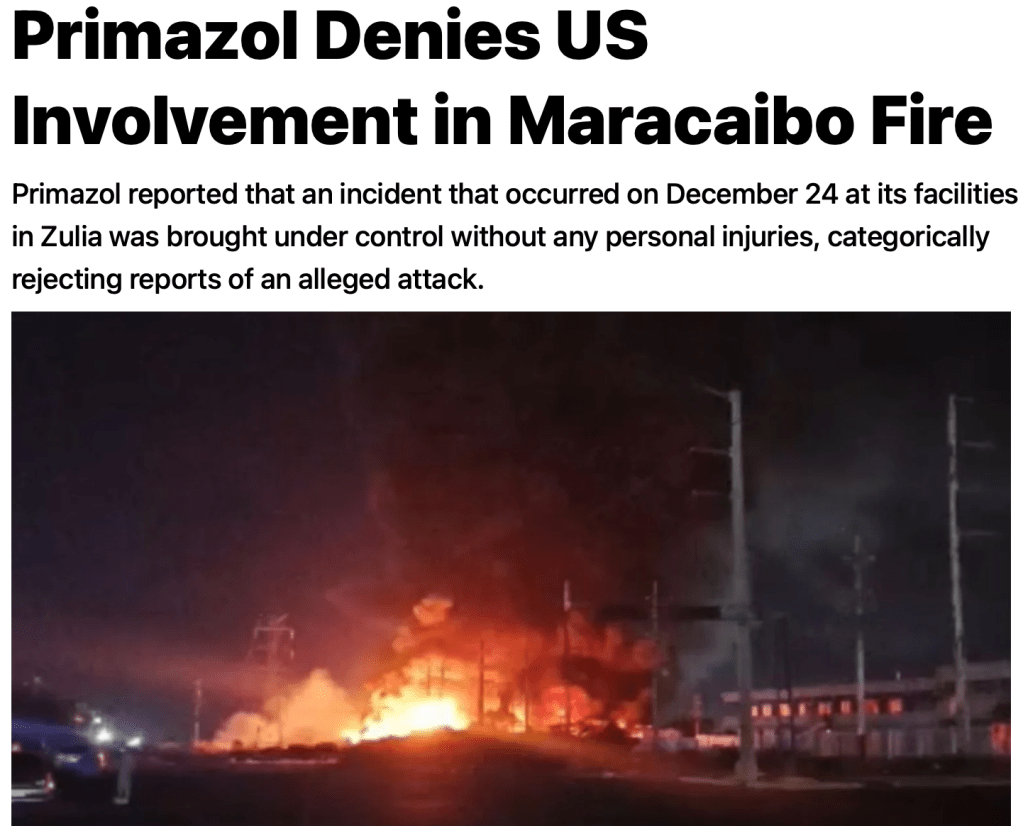

The comments follow more than six decades of U.S. sanctions aimed at inducing regime change in revolutionary Cuba, the kidnapping four weeks ago of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, and Trump’s threat to impose tariffs on any country that continued to sell oil to Cuba.

On Wednesday night, Jan. 29, he declared a “national emergency” to protect “U.S. national security and foreign policy from the Cuban regime’s malign actions and policies.”

Cuban leaders have condemned and denounced this new escalation of the “U.S. economic blockade.”

“Surrender will never be an option, and hard times like these must be faced with courage and bravery,” said President Miguel Díaz-Canel Saturday.

The Trump regime’s tactic of confiscating Venezuelan oil tankers has worsened a fuel and electricity crisis in Cuba. The Cuban people face rolling blackouts and struggle to cope without reliable fuel and electricity supplies.