by Jim Hodgson

In the face of deep inequality within and among the nations of the world, leaders of the so-called “less developed countries” find they must still appeal for basic fairness from their richer neighbours.

More than 75 years after the United Nations was formed, and almost that long since the first development programs were implemented (e.g., the Colombo Plan, 1950), and almost 60 years since the first gathering of the Group of 77 developing nations, leaders gathered last week in Havana and this week in New York to plead their case again.

Not that you would have read about the Havana meeting in mainstream media, but representatives from 114 countries attended the G77+China meeting in Havana. Among them were 30 heads of state or government, as well as senior officials from international organisations and agencies, including UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

The meeting was held under the banner title, “Current development challenges: The role of science, technology and innovation,” but the talk was all about the systems of wealth and power that are rigged against developing countries.

In their final declaration Sept. 16, the G77 demanded fair “access to health-related measures, products and technologies” – a problem highlighted by “vaccine apartheid” during the Covid pandemic when richer countries had first access to vaccines.

G77 called for an end to “existing disparities between developed and developing countries in terms of conditions, possibilities and capacities to produce new scientific and technological knowledge.”

They revived calls for a “new international economic order” and “new financial architecture,” including “through increasing the representation of developing countries in global decision and policy-making bodies which will contribute to enhance the capacities of developing countries to access and develop science, technology and innovation.”

Among the countries participating (including the host, Cuba) were several that have been harmed by sanctions that are usually imposed by wealthier countries to try to provoke changed behaviour by less powerful countries. Sanctions (referred to in the declaration with the UN Human Rights Council term “unilateral coercive measures”), together with external debt, inflation, displacement of peoples, inequality and “the adverse effects of climate change” are all among the “major challenges generated by the current unfair international economic order” and there is “no clear roadmap so far to address these global problems.”

Criticism of the existing international order carried over from the G77 meeting to the UN General Assembly, which met days later in New York.

“They don’t have the $100 billion to aid countries so that they can defend themselves against floods, storms and hurricanes,” said Colombian President Gustavo Petro, referring to the Loss and Damage Fund promoted at the COP climate negotiations to “new and additional” funding from donor nations.

Wars and climate change, he said, are related to that other unprecedented crisis: migration. “The exodus of people toward the north is measured with excessive precision in the size of the failure of governments. This past year has been a time of defeat for governments, of defeat for humanity.”

The political systems that we use to effect policy changes are failing to respond to the urgent needs of our time. Most politicians are beholden to the corporations and rich people who fund their political parties and perpetuate their hegemony. In four-to-six year electoral cycles, the deep changes needed to confront those problems are rarely undertaken.

In Canada, think of the power that mining corporations have wielded to block meaningful investigation of human rights and environmental abuses by their subsidiaries overseas. Or the influence land speculators have over the Ontario government. Or the actions of oil, gas, coal and pipeline companies to stall meaningful action to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

And then scale that up globally. Think of the ways pharmaceutical companies blocked access to HIV and AIDS medications until a global fund was found to pay them – and then pulled the same stunt over Covid vaccines. At the UN on Sept. 20, Guterres said time was running short for climate action thanks to the “naked greed” of fossil fuel interests.

What is delivered through Official Development Assistance and Sustainable Development Goals may be crumbs and band-aids. While necessary, those funds are not sufficient to counter instruments of power like corporations and their allies in the international financial institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Political change is required to make the systems change.

As Xiomara Castro, president of Honduras, told the G77 in Havana: “The time has come to put an end to the backyards [using a U.S. term referring to its relationship to Latin America] because we are not pieces on a chessboard of those who are apologists for dependence. Our nations should not continue to suffer the mass privatization of their territories.”

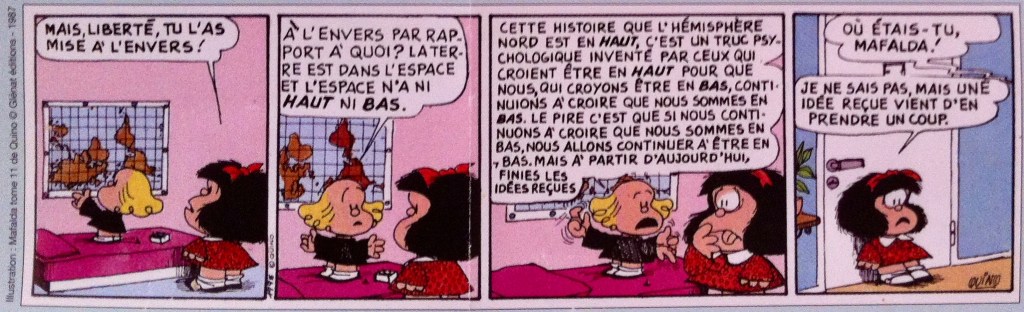

Liberty: Upside down compared to what? Earth is in space where there is no up or down.

Liberty: That story that says the north has to be above is a psychological trick invented by those on the top to make those who are on the bottom continue to believe that we are the bottom. But, beginning today, conventional ideas are over!

Last panel, a voice: Where were you, Mafalda?

Mafalda: I don’t know, but a conventional idea has taken a blow.

(For that last line, Quino, the great Argentinian cartoonist who created Mafalda, wrote in the original Spanish version, “No lo sé, pero algo acaba de sanseacabarse” – the sense being that something has ended.)