by Jim Hodgson

Perhaps I should be grateful to the Norwegian Nobel Committee for again putting Venezuela into the headlines with its absurd award of the Nobel Peace Prize to María Corina Machado, a woman who has never rejected violence as she sought the overthrow of successive Venezuelan governments since 1998.

The prize came as the United States stepped up its attacks on fishing boats it alleged (without evidence) were carrying drugs from the Venezuelan coast to the United States. It came as the Trump administration ended a “quiet diplomacy” effort with President Nicolás Maduro that was led by Richard Grenell – a victory for hard-liners like Secretary of State Marco Rubio. If the United States opts for war. In the words of James B. Greenberg: “it will not be because diplomacy failed. It will be because war itself is the preferred instrument.”

And today, the New York Times reports that Trump has authorized “covert CIA action” in Venezuela. U.S. officials “have been clear, privately, that the end goal is to drive Mr. Maduro from power.” (That, by the way, is not news: it’s been the goal all along.)

I was astonished by the award, but then also by the responses.

Most “progressive” U.S. commentators, including historian Heather Cox Richardson, celebrated Machado simply because she was not Donald Trump. Likewise Occupy Democrats, The Other 98%, and U.S. Democratic Socialists: one of them (I forget which) erred in saying she was Colombian.

In the United States, author Greg Grandin told Democracy Now that the Nobel prize was the “opposite of peace.”

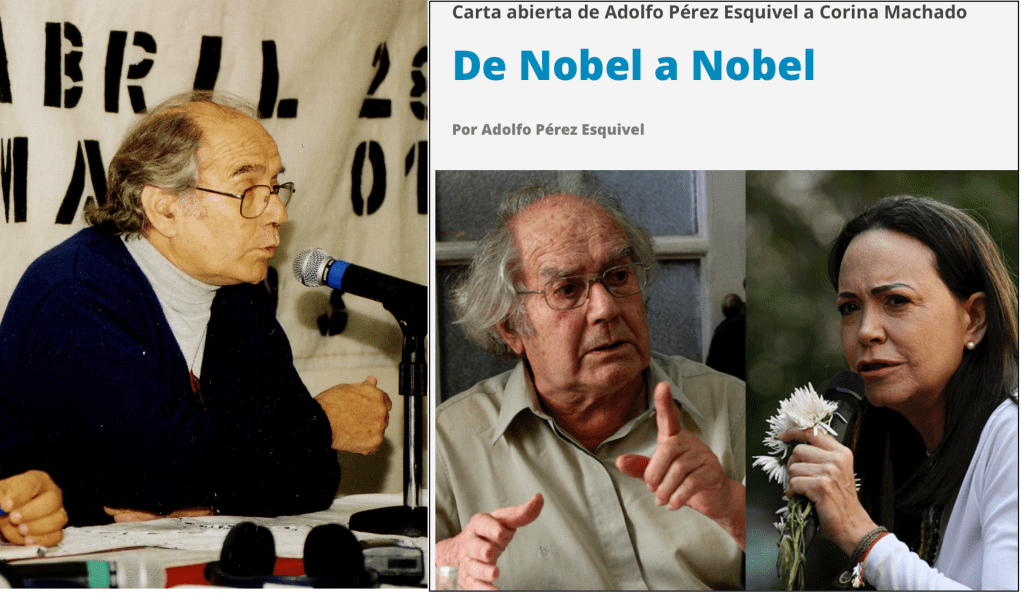

But still: how can the Nobel committee see her together with previous Latin American winners like Rigoberta Menchu and Adolfo Pérez Esquivel who allied themselves persistently with the social movements of the poor, the workers, the Indigenous people, women?

From one Nobel peace prize winner to another

Let’s hear from Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Nobel peace prize winner in 1980 for his non-violent defense of democracy and human rights in the face of Latin America’s military dictatorships, especially the regime of Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina. He published an open letter to Machado on Oct. 13 in the Buenos Aires daily, Página 12. The text is partly translated to English here, source of the following excerpts:

“In 1980, the Nobel Committee granted me the Nobel Peace Prize; 45 years have passed and we continue serving the poorest, alongside Latin American peoples. I accepted that high distinction in their name — not for the prize itself, but for the commitment to shared struggles and hopes to build a new dawn. Peace is built day by day, and we must be coherent between what we say and what we do,” he asserted.

“At 94, I am still a learner of life, and your social and political stance worries me. So I am sending you these reflections,” he emphasized.

In the letter, he argued that the Venezuelan government, led by President Nicolás Maduro, “is a democracy with lights and shadows,” and he underscored the role of former president Hugo Chávez, who, he said, set a path of freedom and sovereignty for the people and fought for continental unity.

“It was an awakening of the Patria Grande,“ he emphasized.

At the same time, he asserted that the United States has not only “attacked” Venezuela but also refuses to allow any country in the region to step outside its orbit and colonial dependence, treating Latin America as its “backyard.” He also highlighted the more than 60-year blockade against Cuba, which he called an attack on the freedom and rights of peoples.

In one of the letter’s toughest passages addressed to Machado, he rebuked her for clinging to Washington even as it confronts her country.

“I am surprised by how tightly you cling to the United States: you should know it has no allies and no friends — only interests. The dictatorships imposed in Latin America were instruments of its drive for domination, and they destroyed lives and the social, cultural and political organization of peoples who fight for freedom and self-determination. Our peoples resist and struggle for the right to be free and sovereign, not a colony of the United States,” he wrote.

On that point, he said the government of Nicolás Maduro «lives under threat» from Washington and from the “blockade,” with U.S. naval forces in the Caribbean and «the danger of an invasion of your country».

“You have not said a word, or you support the interference of the great power against Venezuela. The Venezuelan people are ready to confront the threat,” he warned.

He also criticized that, after receiving the prize, the far-right leader dedicated it to U.S. President Donald Trump. “Corina, I ask you: why did you call on the United States to invade Venezuela?”

“Upon the announcement that you were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, you dedicated it to Trump — an aggressor against your country — who lies and accuses Venezuela of being a narco-state,” Pérez Esquivel said. He compared that accusation to George W. Bush’s false claims that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, used as a pretext for an invasion that looted that nation and caused “thousands of victims.”

“It troubles me that you did not dedicate the Nobel to your people but to Venezuela’s aggressor. I believe, Corina, that you must analyze and understand where you stand,” the Argentine insisted, arguing that her posture makes her “another piece of U.S. colonialism.”

“You resort to the worst when you ask the United States to invade Venezuela,” he added.

Pérez Esquivel concluded: “Now you have the chance to work for your people and build peace — not provoke greater violence. One evil is not resolved with a greater evil; we would only have two evils and never a solution to the conflict. Open your mind and your heart to dialogue and to meeting your people; empty the jug of violence and build the peace and unity of your people so that the light of freedom and equality can enter.”