Even in the face of the Trump regime’s horrific arrests, extraordinary renditions, and forced disappearances of immigrants and asylum-seekers, there are shreds of hope.

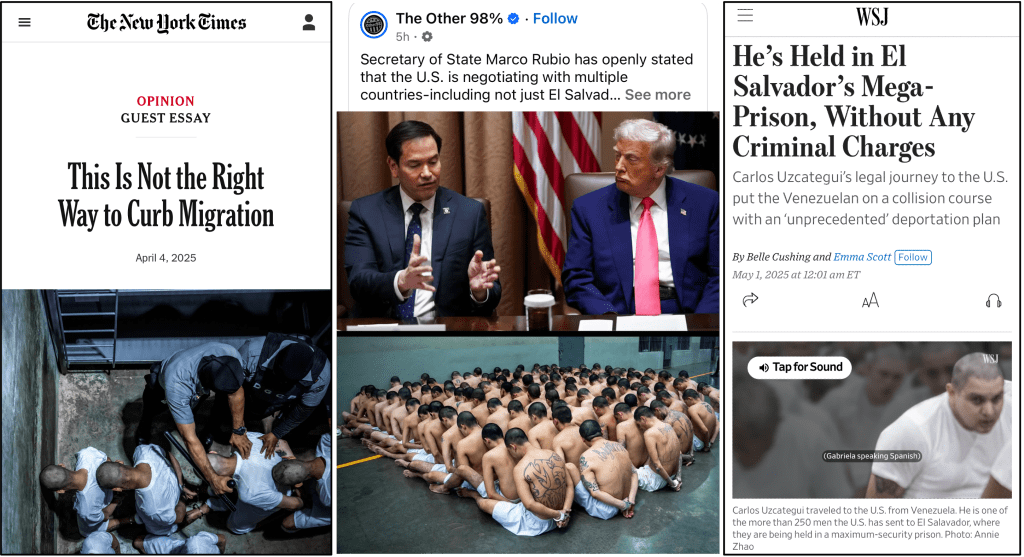

Activists and journalists are gradually identifying and sharing the stories of victims, including the 238 Venezuelans and 23 Salvadorans shipped to a prison in El Salvador on March 15. And judges and some politicians are more vocal in support of “due process”—the U.S. constitutional guarantee of at least being heard before being deprived of liberty—for all migrants.

Above on the left is Andry Hernández Romero, age 31. I learned of his case the way many others did. A photojournalist, Philip Holsinger, met the airplanes that brought the Venezuelans to El Salvador and then accompanied them to the prison. A man who caught Holsinger’s attention shouted “I’m innocent” and “I’m gay,” and was crying as his head was shaved. From Holsinger’s photo, friends and family members identified him as Andry. Details of his situation were covered first in LGBTQIA+ media (The Advocate and the Washington Blade) and later by NBC, CBS and elsewhere. His lawyer has mobilized political support in California, including that of Gov. Gavin Newsom and U.S. Rep. Robert Garcia.

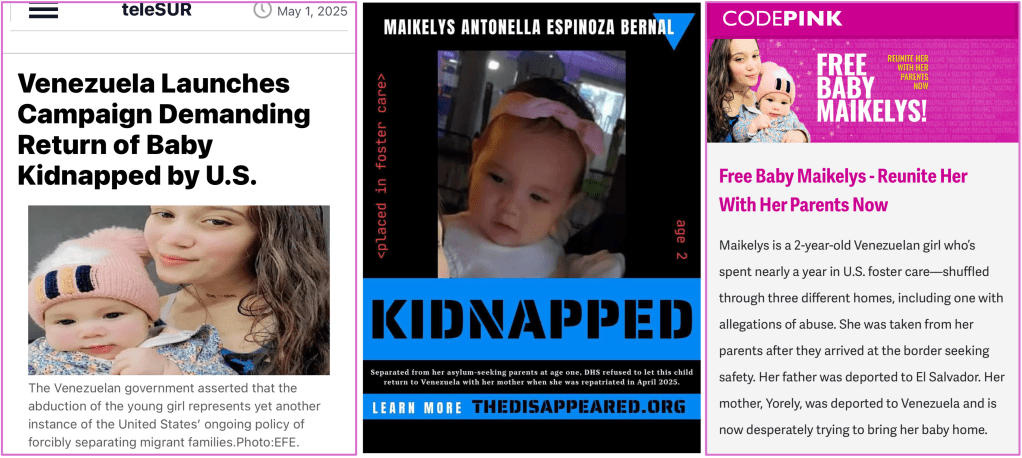

The disappeared.org site draws attention to many other cases, including that of two-year-old Maikelys Antonella Espinoza Bernal (below) whose father, Maiker Espinoza Escalona, was sent to the prison in El Salvador. She and her mother Yorely Bernal Inciarte, were supposed to be sent together on a deportation flight back to Venezuela—part of her homeland’s “Vuelta a la Patria” program for citizens willing to go home. But the United States refused to return the child to her mother before she left.

The Disappeared shared a piece from a group called United Strength for Action about the U.S. role in creating the disaster that Venezuelans face. I can’t concur with all the group said–many people in the United States just can’t see the historical context of U.S. imperialism–but I am relieved that they at least acknowledged the role of U.S. sanctions in creating a humanitarian crisis that drives the exodus of refugees. “This wasn’t foreign policy; it was collective punishment that pushed millions of Venezuelans past their breaking point.”

Since 1998, successive U.S. administrations have done all they could to be rid of Nicolás Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chávez: a coup attempt in 2002, a “revocatory” referendum in 2004, the effort to impose a “president” (Juan Guaidó) whom nobody had voted for, and through waves of sanctions. Given the failure of those efforts to induce regime change and seeing the flow of migrants out of Venezuela, President Joe Biden for a time tried a different approach, one of dialogue and engagement. The early weeks of Trump’s administration gave some hope this could continue, but the hard-liners seem to hold sway once again.

At a May Day march, President Maduro vowed to “rescue” Maikelys along with the Venezuelans now held by El Salvador. He also spoke directly to the hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans who have tried to reach the United States in recent years:

“Stop going there. The true dream is that of our land to build with our hands. Stop being victims of xenophobia, of abuse… The only land that will welcome you and serve you like the prodigal son is called the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. We must take care of it, fertilize it, and build it. This homeland belongs to all!”

Maduro emphasized Venezuela’s right to build its own social model. “We have the right to true democracy, to our cultural identity. We are not gringos. We are proudly Bolivarian, Latin American, Caribbean. We are Venezuelans!”

Venezuela says it is willing to receive people deported from other countries. Between February and April 25 this year, 3,241 Venezuelans had returned on 16 government-funded flights. Yorely (the mother of Maikelys) came home on just such a flight.

Two more issues. Trump officials say that the people sent to jail in El Salvador were linked to the Tren de Aragua criminal gang, and that they used tattoos to identify the gang members.

Trump’s executive order decreeing the deportations said the gang is “conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States.”

But that is not true. In an article for The New York Times, a team of experts on violence in Venezuela said Tren de Aragua is not invading the United States. Nor is it a “terrorist organization,” and to call such “criminal groups terrorist is always a stretch since they usually do not aim at changing government policy.” The article goes on to show that Tren de Aragua is not centrally organized, though members were involved in migrant smuggling and the sexual exploitation of Venezuelan migrants in Colombia, Chile and Peru.

The NYT piece adds that even U.S. intelligence officials do not believe the Maduro government is colluding with the gang, the key assertion in Trump’s justification for invoking the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to render Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador.

Immigration officials used tattoos to “determine” if someone was linked to Tren de Aragua, but the authors of the NYT piece say Venezuelan gangs (unlike Salvador groups like the MS-13) do not use tattoos that way. “Many young Venezuelans, like young people everywhere, borrow from the global culture of iconic symbols and get tattoos. That doesn’t mean they’re in a gang,” they wrote.

Moreover, the Tren de Aragua gang network in Venezuela is largely dismantled.

“The Tren de Aragua is cosmic dust in Venezuela; it no longer exists, we defeated it,” President Maduro said March 19. He was quoted by the English-language Orinoco Tribune in a longer article about the gang’s history in Venezuela.

Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello questioned whether all deportees were Tren de Aragua members, and demanded the US extradite captured suspects. “The US is acting in a confusing manner. They promised to send us Tren de Aragua members, but they have not. Someone there is lying.”

* Update, May 14 * Two-year-old Maikelys has been re-united with her mother in Venezuela. Her father remains in the Trump-Bukele prison in El Salvador. See the statement from CodePink.