The Mexico City daily newspaper, La Jornada, published an interview May 9 with Cuba’s vice-minister of external relations, Carlos Fernández De Cossío.

Cuba’s lack of peace, he emphasized, is caused by Washington’s policies against the people of Cuba, characterized by economic coercion with the blockade. He warned that while practically the whole world has been the object of tariff threats by the administration of Donald Trump, “towards Cuba, the onslaught is already underway, and only military aggression is lacking” to complete the siege.

In the face of new global geopolitics, with Trump in power, he warned that the White House now attacks several countries: “you see this in Panama, Greenland, Canada;” the focus could also be the progressive governments elsewhere in Latin America.

“There are threats against several governments, and the United States will attempt, through force, economic pressure, and other methods, to influence the political processes of our countries. Venezuela is a country under attack. It’s evident that the region faces that reality…. The absence of armed conflict does not mean living in peace.” He also said that there is pressure on nations in the hemisphere to adopt measures to “reduce the ‘harmful influence’ of China.”

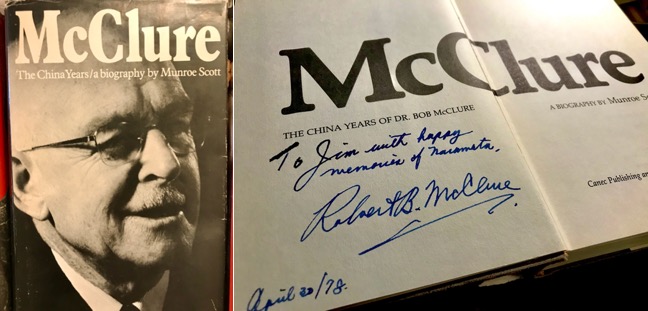

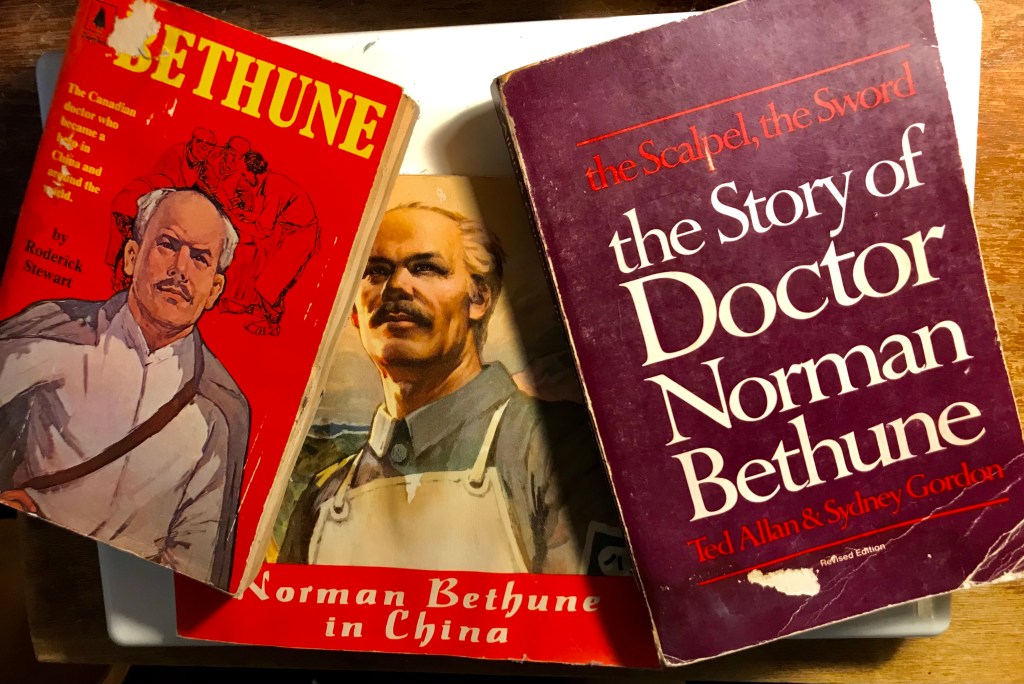

Over the past two-and-a-half years, I have worked with my former colleagues at The United Church of Canada, other churches, several trade unions and international development organizations to draw attention to the impact of U.S. sanctions (“the blockade”) on the Cuban people. Now that Canada’s new cabinet ministers are confirmed, we’ll likely launch a new call to “take action” in solidarity with Cuba.

Fernández de Cossío was in Mexico City for meetings May 8 with Mexico’s External Relations department (SRE) to talk about migration issues.

With a long career in diplomacy, Fernández de Cossío has served as director for the United States in the Cuban foreign ministry. He also served as ambassador in Canada (2004-05) and South Africa, and was Cuba’s representative in the peace process between the government of Colombia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

He said spaces like the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) are key to creating a counterweight to Washington. “They must move beyond declarations and formality. Getting there is not easy.” What follows is a lightly-edited translation of his interview with La Jornada writers, Emir Olivares and Arturo Sánchez Jiménez.

Migration challenges

Q: What are the challenges to the region from the new anti-migration policies of Trump?

R: If the great gap between the industrialized, developed countries and the countries in processes of development is not reduced, it’s natural that there will be a growing flow from the south toward the north to seek better living conditions. That goes on in Africa, in Asia and in our continent, where the flow toward the United States, whether it be regular or irregular. The reality varies by each country.

Q: And for Cuba?

R: The case of Cuba is unique. The United States has applied a dynamic against it that both pushes and pulls migration, whether regular or irregular. Washington’s official policy is economic coercion. The blockade, aimed at depressing and making living conditions as difficult as possible, provokes a migration drive.

Furthermore, since the 1960s, Cuban immigrants have been privileged, regardless of how they cross the border, by sea or by land. They are assimilated, granted refugee status, protected, and provided with employment. Additionally, there is the Cuban Adjustment Act, which means that regardless of how they entered the United States, Cuban migrants can acquire residency within one year of arriving in the United States. No citizen of any other country in the world has that privilege. If Washington does not put an end to this reality, the irregular flow will continue.

Q: What do you think of the U.S. propaganda shared in mass media and internet platforms against migration, headed by the secretary of homeland security, Kristi Noem?

R: It’s media opportunism that seeks support in the population. They unfairly criminalize all immigrants. To a certain extent, society has been polarized since its inception, with cultural and racial prejudices. And it’s not difficult for these politicians to try to stir up those feelings to promote a policy of rejecting immigrants and blaming them for many of the problems: drug use, unemployment, crime, and social polarization. If some migrants participate in crime and social unrest, it’s because these phenomena already exist in the United States.

Historically, the United States has believed that Cuba belongs to them, but in reality, it is an inability to accept that Cuba is, and has the right to be, a sovereign state.

Campaign against the health brigades

Q: The campaign against Cuba’s medical brigades is within these new coercive measures?

R: Yes. Since February, they have threatened that countries that continue medical cooperation programs with Cuba, their officials and family members will lose their visas and their ability to travel to the United States. Today, around 60 nations have these programs. They provide care to thousands of people. It is a historic project, for which Cuba has been praised by governments, several UN secretaries-general, and even a US president (Barack Obama).

The campaign seeks two things: to discredit this symbol of the success of Cuban society, since one of the priorities of anti-Cuban sectors is to prevent recognition of Cuba’s successes. The second is to cut off a legitimate source of income obtained from agreements with countries that are more favourable (such as Mexico), although historically these are services for which not a cent has been received.

Q: Do Trump’s new geopolitics bring additional pressures to the hemisphere?

R: It’s part of the US government’s hostile and imposing behavior toward the region, and it’s a challenge not only for Cuba but for the entire region. There’s pressure to adopt measures to reduce “China’s harmful influence.” We find it absurd. In a recent congressional hearing, they showed alleged Chinese military bases in Cuba (they used to say they were Russian, during the Cold War). They presented images of what could have been a soccer field or a rice field to say: “This is evidence that there are Chinese military bases in Cuba,” but there wasn’t a single military officer there, no one from the Pentagon or the CIA, from the institutions that are supposed to bear witness to this.

There’s threatening behavior that tries to impose their will on the hemisphere. We saw this in Panama. We see it in Greenland (even though it is not part of the region) and with Canada. It’s a challenge for us all and it’s dangerous.

Q: What have been the errors of the revolutionary regime?

R: Fidel Castro once said that the biggest mistake was thinking that anyone knew how to build socialism and that it would be easy to do so. In Cuba, specific errors may have been made in some aspects of economic policy, in elements of social policy, but it’s very difficult to judge if one takes into account the challenges posed by the aggression of a power like the United States.

Q: Are the ideals of Martí, Castro and others still valid?

R: The ideas of Martí, Fidel, Marx, Engels, Lenin and other Marxists remain relevant and continue to shape our thinking. The challenge we face with youth is enormous, due to the communication influence that large corporations have exerted, a monopoly that is difficult to break. This, combined with a very depressed economic situation, has a serious and dangerous impact on the population. We are working with this; we accept it as a challenge, a very great challenge facing Cuban society.